- EGX rallies nearly 5% on news of more IMF funding. (Speed Round)

- Foreign reserves slipped again in May, but at a slower pace. (Speed Round)

- Egypt’s covid-19 deaths at 1,237 (+39); cases reach 34,079 (+1,467). (What We’re Tracking Today)

- EBRD to provide NBK Egypt with USD 100 mn for onlending to private sector. (Speed Round)

- Expect to see Egypt’s GDP growth recover significantly in mid-2021, Maait says. (Last Night’s Talk Shows)

- How does the Egyptian economy achieve escape velocity from the covid-19 downturn? (The Macro Picture)

- Weakening USD sends investors flooding into EM currencies. (What We’re Tracking Today)

- Why do Egypt’s international private universities lag in global rankings? And does it even matter? (Blackboard)

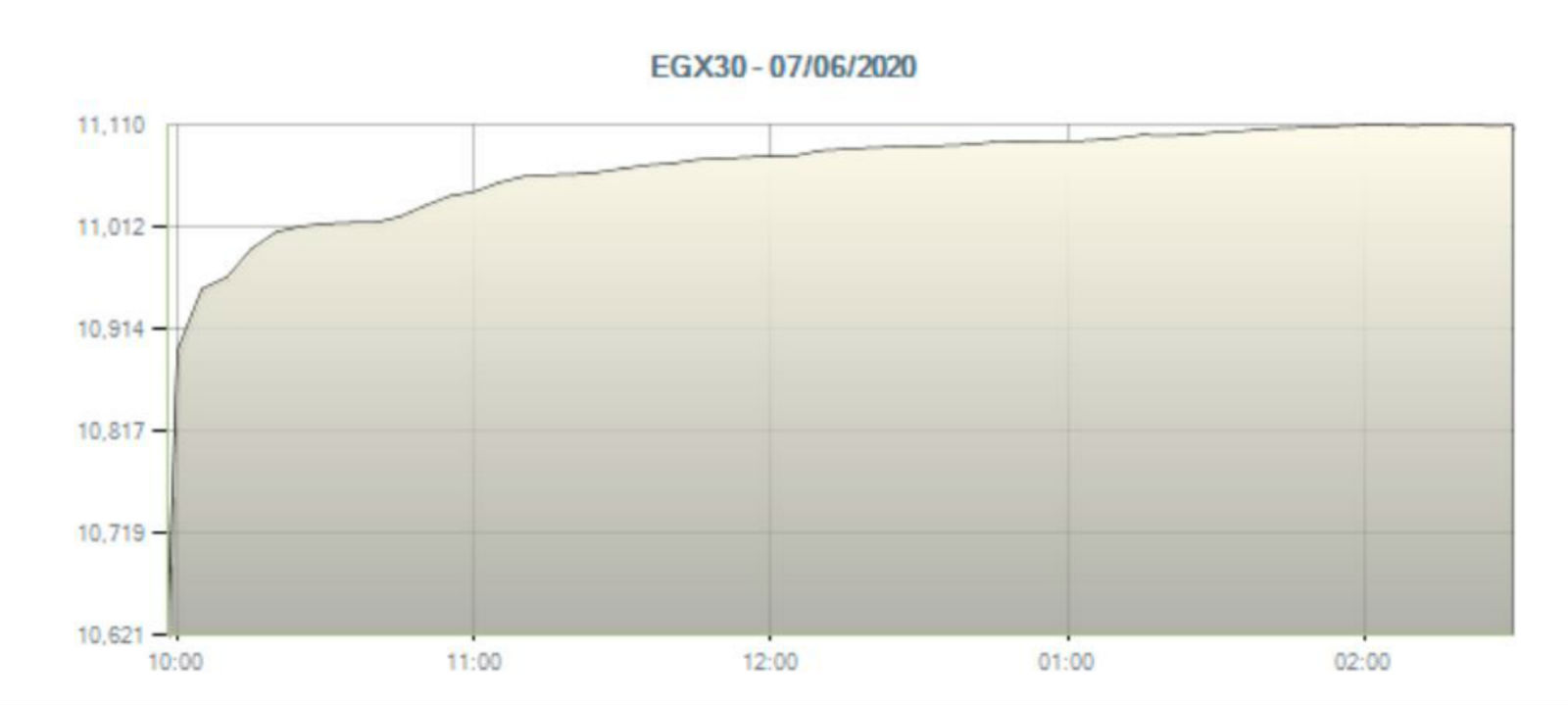

- The Market Yesterday

Monday, 8 June 2020

EGX rallies on IMF funding, Maait guides for significant pickup in growth in mid-2021

TL;DR

What We’re Tracking Today

Good morning, friends. Let’s take stock of where we stand as we slide into summer. The global covid case count stands at 7 mn this morning, or less than 0.1% of the global population, with total deaths standing at a little over 402k. Brazil reported the largest number of total new cases yesterday at about 27k. MSCI’s World Index of global stocks is down 6% since Wuhan went into lockdown at the end of January, and global GDP contracted about 2.3% last month.

Here at home, shares are down a hair over 20% year-to-date, our economy is one of the only ones in the region expected to post even slightly positive growth this year, and our daily case total has stabilized for the moment at just under 1.5k per day with around 40 people per day succumbing to the infection.

The challenge: Managing our continued reopening. Global experience points the way: California, Florida and Texas are among many states that have posted rises in infections since starting to reopen their economies. New York is bracing as it prepares to reopen today amid continuing protests for racial equality and an end to police violence. And South Korea is dealing with an uptick.

The House is back in session — and their agenda is packed:

- A bill to set up a tourism support fund could go up for a final vote as early as today, Rep. Galeela Osman told Al Mal. The bill received approval yesterday from the House committees for tourism, culture, and media, Al Mal reports.

- The FY2020-2021 state budget is up for discussion next week, House Speaker Ali Abdel Aal told the general assembly yesterday.

- MPs are set to discuss the reconstitution of the upper house of parliament and a number of business-related bills this week as they close in on their summer vacation. We have more on this in this morning’s Speed Round, below.

The markets this morning: Asian shares are cautiously in the green in early trading this morning and Gulf shares posted major gains yesterday after Saturday’s OPEC+ agreement that will see producers limit oil production through July. Futures suggest shares in Europe and the US will open in positive territory later today, and the EGX shot up nearly 5% yesterday on news of fresh funding from the IMF (we have the rundown in this morning’s Speed Round, below).

The inaugural EFG Hermes Virtual Investor Conference will run for six days between 22-30 June. The event will feature one-on-one virtual meetings between investors and business leaders during three two-day sessions running 22-23 June, 24-25 June and 29-30 June.

Other key news triggers coming up this month:

- Inflation data for May will land on Wednesday, 10 June.

- The Central Bank of Egypt will meet to review interest rates on Thursday, 25 June.

- Founding members of the EastMed Gas Forum will meet this month to ink the Cairo-based energy organization’s charter.

COVID-19 IN EGYPT-

The Health Ministry confirmed 39 new deaths from covid-19 yesterday, bringing the country’s total death toll to 1,237. Egypt has now disclosed a total of 34,079 confirmed cases of covid-19, after the ministry reported 1,467 new infections yesterday, about on par with the day before. We now have a total of 10,131 confirmed cases that have since tested negative for the virus after being hospitalized or isolated, of whom 8,961 have fully recovered.

Banks to cover infected staff: Central Bank Governor Tarek Amer has instructed the country’s banks to cover the medical costs of employees and their families should they become infected with the virus, Masrawy reports.

EgyptAir is seeking a EGP 3 bn loan from the National Bank of Egypt as it haemorrhages EGP 1 bn per month amid the ban on international flights and anemic domestic traffic, chairman of the holding company Roshdy Zakaria told the local press. The funding would be used to service debt. Zakaria said that the national flag carrier has already drawn down an EGP 2 bn lifeline from the state to fund covid-related obligations, including paying staff salaries.

In other news from the tourism industry:

- Industry observers expect air travel to resume by mid-July.

- Some hotel operators say it’s not financially feasible to reopen during the pandemic

- Poland is said to be ready to resume direct charter flights to the Red Sea as early as the end of June.

- More than 162k tourism workers have benefitted from EGP 171 mn in financial aid from the Manpower Ministry.

Repatriation flights: EgyptAir and Air Cairo are running flights 14-20 June to bring back as many as 3k citizens from Jordan; Air Cairo is bringing home 1.9k citizens originally in Qatar via Oman.

ON THE GLOBAL FRONT-

Imperial College London to bypass Big Pharma to provide cheap, accessible covid-19 vaccine: Imperial College London is preparing to bring to market a potential covid-19 vaccine at the lowest possible cost in Britain and in low- and middle-income countries. Private companies have dominated the R&D of potential covid-19 vaccines, raising fears that they will eventually be distributed based on profit, rather than on need. Its vehicle: a newly-created social enterprise VacEquity Global Health.

GLOBAL MACRO-

Weakening USD sends investors flooding into EM currencies: Emerging-market currencies saw their best week in more than four years last week as the weakening USD sent investors storming into risk assets, Bloomberg reports. EM assets added at least USD 1 tn in value during the week as currencies joined a rally that had been spurred by stocks and bonds. EM equities added around USD 800 bn during the first four days of trading while bonds added USD 40 bn.

Uncertainty over trajectory of virus in Africa fails to dent exuberance: More than half of the top-performing developing-country bond markets this quarter are in Africa, where daily infection rates continue to climb. “[Investors] seem prepared to ignore rising cases in lower-income countries where ineffective lockdowns have been dropped,” said Charles Robertson, global chief economist at Renaissance Capital

Global remittances could fall 20-30% this year -IIF: The flow of global remittances could fall between 20-30% this year as economies across the world enter simultaneous contraction, the Institute of International Finance has said. By comparison, receipts fell only 5% during the global financial crisis, suggesting that countries with high external funding needs such as Egypt, the Philippines and much of Central America could face pressure, the IIF said.

US policymakers need to act fast to prevent the economic crisis from further entrenching economic inequalities -El Erian: The economic damage wrought by the pandemic has overwhelmingly fallen on the poorest and most vulnerable communities in the US — if policymakers don’t act decisively to ramp up contact tracing and expand welfare programs the US faces deepening economic, institutional and social instability, Mohamed El Erian and Michael Spence write in Foreign Affairs.

AND THE REST OF THE WORLD-

Protests against racial injustice and police brutality continued to flare up across US cities and European capitals: Thousands of protesters continued to peacefully gather calling for racial justice and police reform in major cities and small towns across the US, the Guardian reports. The UK, Italy, Spain, Belgium, Denmark and Hungary also saw demonstrations. Protesters toppled a statue of a colonial-era slave trader in Bristol and the defaced a likeness of King Leopold II statue in Belgium. South Korea, Australia and Japan saw gatherings fan out in city centers.

80% of Americans think their country is “spiraling out of control” and “voters by a 2-to-1 margin are more troubled by the actions of police in the killing of George Floyd than by violence at some protests,” according to a Wall Street Journal / NBC News poll.

*** It’s Blackboard day: We have our weekly look at the business of education in Egypt, from pre-K through the highest reaches of higher ed. Blackboard appears every Monday in Enterprise in the place of our traditional industry news roundups.

In today’s issue: Should we care where Egyptian universities fall on global rankings of higher education?

Enterprise+: Last Night’s Talk Shows

The highlight of last night’s talk shows was Finance Minister Mohamed Maait’s chat with Al Kahera Alaan’s Lamees El Hadidi for an update on Egypt’s macro indicators and the government’s outlook amid covid-19.

The government is constantly updating its forecasts for Egypt’s economic growth as developments in the global economy rapidly unfold — some of which are positive, including the better-than-expected jobs data from Canada and the US, Maait said. The minister reiterated government expectations that Egypt will close out the current fiscal year (it ends on 30 June) with 4-4.2% GDP growth, down from original expectations of 6% growth.

Expect to see GDP growth recover significantly in mid-2021, or by the beginning of FY2021-2022, the minister said. Planning Minister Hala El Said had previously said the majority of Egypt’s growth in the coming fiscal year (3.5%) will likely be concentrated in its second half, with “very low growth” expected in the first half of the government’s new fiscal year, which runs July-December of this calendar year.

Egypt is still actively looking at financing from other international institutions beyond the IMF to help plug its budget deficit, after having secured a USD 2.8 bn rapid financing instrument and reaching an initial agreement over an additional USD 5.2 bn standby agreement from the fund, Maait told Lamees.

Tap or click here to watch the full interview (runtime: 27:34).

PepsiCo is investing USD 100 mn in Egypt this year to expand its production lines, GAFI boss Mohamed Abdel Wahab told El Hekaya’s Amr Adib. The investment is part of a total USD 515 mn the company pledged to invest over four years back in 2018 (watch, runtime: 2:41).

The Education Ministry is moving exams for three Thanaweya Amma subjects to at-home exams as it looks to reduce the number of students that pour into testing rooms, Minister Tarek Shawki told Lamees (watch, runtime: 17:55).

Speed Round

Speed Round is presented in association with

EGX rallies nearly 5% on news we reached a preliminary agreement for more IMF funding: The EGX30 rose 4.6% in heavy trading yesterday after the International Monetary Fund (IMF) announced on Friday it had reached a staff-level agreement to provide Egypt with a one-year, USD 5.2 bn loan. The benchmark index is now down 20.4% for the year, largely in response to the pandemic’s economic fallout and a shutdown of the tourism industry, Reuters notes.

Biggest gainers: The EGX30’s top performing companies were Pioneers Holding (+8.6%), EFG Hermes (+8.2%), and TMG Holding (+6.2%). Trading was heavy, with EGP 1.4 bn-worth of shares changing hands, about 89% above the trailing 90-day average.

The announcement of the standby agreement with the IMF also helped slow the USD’s rally against the EGP, which was was changing hands at 16.17 against the greenback yesterday, inching up two piasters from 16.15 / USD 1 on Thursday, according to CBE data (pdf). The EGP had held steady at 15.70 throughout the onset of the covid-19 pandemic, after peaking at 15.49 on 23 February.

What to expect from the IMF loan: The loan, which still needs a final sign-off from the fund’s executive board (expected some time this month), would come in the form of a stand-by arrangement (SBA) to help withstand the economic fallout from the covid-19 pandemic and safeguard Egypt’s recent economic gains and reform program. It comes on top of the USD 2.8 bn rapid financing instrument Egypt received last month to help plug in the budget gap and support temporary spending to fight the pandemic.

Foreign reserves slipped again in May, but at a slower pace: Foreign reserves edged down USD 1 bn to USD 36 bn in May, the third consecutive month of decline, albeit at a slower rate, according to Central Bank of Egypt (CBE) data. The central bank did not explain the dip. Egypt’s reserves fell by USD 3.1 bn in April after dropping USD 5.4 bn in March from a peak of USD 45.5 bn in February. Reuters also has the story..

Not yet included in our reserves base: Proceeds from the record USD 5 bn eurobond Egypt sold last month in its largest-ever issuance, Masrawy reports, citing unnamed sources. The issuance was 4.4x oversubscribed, attracting bids for around USD 22 bn worth of bonds.

Background: The CBE had previously dipped into reserves to meet USD 1.6 bn in external obligations, including a USD 1 bn eurobond that matured in April. It also provided an undisclosed sum of FX to back the purchase of strategic commodities. Foreign investors also pulled USD 17 bn out of Egypt since the beginning of the covid-19 crisis in March.

The EBRD will provide the National Bank of Kuwait Egypt with USD 100 mn for onlending to the private sector, according to a statement by the International Cooperation Ministry. Minister Rania Al Mashat had said in April that the EBRD has expanded its short-term liquidity funding package for its Southern and Eastern Mediterranean countries, including Egypt, following talks with multilateral lenders.

In separate news, EBRD awarded Egypt two international sustainability awards, a statement by the bank said. The Egyptian Electricity Transmission Company won a silver award for promoting green skills for women in the renewable energy sector, and the Egyptian National Railways won a bronze award for cracking down on harassment on the country’s rail network. The lender recognized a total of 16 clients in 11 countries for environmental and social sustainability.

LEGISLATION WATCH- House approves sovereign fund law, Public Enterprises Act, ships them off to Maglis El Dawla for review: The House of Representatives’ plenary session gave near-final approval yesterday to proposed amendments to the sovereign fund law and shipped the bill to the Council of State (Maglis El Dawla) for a final legal review, according to Masrawy. The amendments provide VAT refunds to any company that is more than 50% owned by the SFE and its sub-funds — set up to attract investment to logistics, renewables and manufacturing — and limits the scope of legal action that can be taken against the fund, shielding the SFE and its coinvestors from third-party lawsuits.

The Public Enterprises Act amendments also earned a near-final vote from parliament’s general assembly and will also be sent to Maglis El Dawla for a legal review, according to Al Mal. The amendments reclassify listed companies in which the government holds up to a 75% stake and bring them within the scope of the Companies Act, introduces a cap on board compensation, and puts in place new regulations requiring state-owned enterprises to provide evidence that their subsidiaries are economically viable.

Both bills will require a final vote from the House once Maglis El Dawla signs off on them.

A bill to constitute the Senate as an upper house of parliament passed yesterday in the House Legislative Committee, Al Shorouk reports. The bill, drafted by the majority bloc Support Egypt Coalition, proposes a 300-member chamber; last year’s constitutional amendments, which brought back the upper house of parliament, specify that it should have at least 180. Members will be reappointed or elected once every five years. The law will now make its way to the House general assembly for approval.

The Tax Authority has pushed to September its deadline for companies to unlock assets by remitting overdue VAT, according to a Tax Authority statement. The deadline was originally this month. Frozen assets will automatically be released by the authority, bypassing the requirement for an official appeal, after 5% of total VAT owed is paid and the remainder is scheduled for payment within a two year period.

REGULATION WATCH- FinMin allows consumer finance companies to deduct a larger portion of interest payments from their tax bills: Consumer finance companies will no longer be bound by a limit that saw the Tax Authority impose a cap on interest expenses it considers tax-deductible, according to a Finance Ministry decision issued Saturday. The limit previously allowed those companies to cross off interest expenses of up to four times their shareholders' equity from the profit calculated for tax purposes. Now, the full value of the interest expense will be deducted from net profit before tax before calculating the taxable income.

What this means: The cap meant that the Tax Authority only approved debt expenses less than four times any given consumer finance player’s net worth. This made lives harder for consumer finance companies, who profit by lending to individuals for the purchase of consumer goods and durables using large credit lines initially taken out from banks. Consumer finance players are now on par with others operating in financial leasing, real estate finance, factoring, securitization, insurance and some banks, the ministry said.

BUDGET WATCH- Gov’t sets aside a quarter of its FY2020-21 investment budget for Upper Egypt: The government is planning to invest EGP 47 bn in Upper Egypt next fiscal year, which starts on 1 July, the Planning and Economic Development Ministry said (pdf). This amount accounts for a quarter of direct government investments, and is a 50% increase from the amount allocated to the underdeveloped region in FY2019-2020.

Samih Sawiris’ talks with SFE to develop Bab El Azab reportedly break down: Samih Sawiris’ plans to invest with the Sovereign Fund of Egypt (SFE) in developing the Bab El Azab landmark in Old Cairo have reportedly hit a snag, Al Mal reports, quoting unnamed government sources. It remains unclear what caused the talks to break down. The bn’aire told Hapi Journal before the covid-19 outbreak took hold that he was planning to ink an agreement by 4 February. News of him stepping away came after the fund signed last week an agreement with the Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA) to begin shopping for private partners. The Bab El Azab revamp project involves building a museum with interactive technologies, craft schools, theaters, and other facilities near the historic site.

STARTUP WATCH- Shezlong raises fresh funds for regional expansion: Online psychotherapy platform Shezlong has raised an undisclosed amount of financing from Asia Africa Investment Consulting, angel fund HIMangel, and investor Mohamed El Khamissy, Menabytes reports. Founder and CEO Ahmed Abu El Haz said the new funds would be used to expand “vertically and horizontally” in the Middle East, and provide new products such as texting-based therapy and corporate wellness programs. Shezlong raised USD 350k last year, and won a USD 100k grant from Expo 2020’s Innovation Impact Grant Program.

CORRECTION- An article we picked up from the domestic press for yesterday’s issue incorrectly said that French energy company Total had been awarded a contract to supply renewable energy to the 1.5 mn feddans project alongside Enara Energy. The story has since been corrected on our website.

In this week’s episode of Making It, our podcast on how to build a great business in Egypt, we spoke to Tarek Assaad and Karim Hussein, two of the three managing partners of the Cairo-based USD 54 mn venture capital fund, Algebra Ventures. Today, their portfolio covers a range of industries connected by a common denominator — a tech-enabled business model that can disrupt the existing market. The two discuss the elements and qualities that make startups appealing for investors and offer advice to entrepreneurs looking to secure funding.

Tap or click here to listen to the episode on our website | Apple Podcast | Google Podcast | Omny. We’re also available on Spotify, but only for non-MENA accounts. Subscribe to Making It on your podcatcher of choice here.

The Macro Picture

How does the Egyptian economy achieve escape velocity from the covid-19 downturn? The answer lies in the “strategic monetization” of public infrastructure, reorienting supply chains and capitalizing on business process outsourcing, Ahmed Galal Ismail, CEO of Majid Al Futtaim Properties, writes for the World Economic Forum. The government should focus on bringing into the fold infrastructure investors who have expertise in turnaround situations and steady value creation, and help pass on critical infrastructure projects (such as upgrading the power grid and improving water sanitation) to the private sector, thereby lowering government spending.

Responding to deglobalization trends: Egypt should look to develop local supply chains and work with Chinese firms to strengthen distribution networks and upgrade manufacturing capacity, Ismail says. Lessening dependence on increasingly fragile global supply chains will allow the government to develop local agriculture and integrate new technologies. On top of this, Egypt should exploit its warm ties with Chinese firms and use them to build stronger regional supply chains.

Capitalizing on demographics: The country’s young, educated population is also a key asset Egypt can use to market itself as an attractive business process outsourcing (BPO) destination for multinationals. With 500k graduates every year and one of the largest IT workforces in the world, Egypt is well-placed to attract new foreign investment in outsourcing, Ismail writes.

Egypt in the News

It’s a pleasantly slow morning for Egypt in the international press. Reuters looks at hotels reopening in this time of covid and what it says is a shortage of domestic cigarettes in 13 governorates, while Israel’s Haaretz looks at the popularity of mahraganat. For photo nerds: The Barber Institute of Fine Arts is displaying a collection of photos from the Prince of Wales’ 1862 tour of the Middle East which took him through Egypt, among other points, Apollo Magazine reports.

Diplomacy + Foreign Trade

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has approved the appointment of Amira Oron as Tel Aviv’s ambassador to Egypt, the first full-time envoy to Cairo in more than 18 months and the first-ever woman to fill the post, according to The Times of Israel. Oron, who was originally tapped for the post back in 2018, was previously in charge of the Egypt desk at Israel’s Foreign Ministry and served as an ambassador to Turkey.

Egypt and Nigeria are squaring off over candidate nominations for the role of World Trade Organization (WTO) Director General, Nigerian publication the Guardian reports. After three candidates — from Egypt, Nigeria, and Benin — were shortlisted for the position, Nigeria asked to substitute existing candidate, WTO Deputy Director General Yonov Frederick Agah, for former World Bank Managing Director Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala. Egypt is arguing that a substitution at this point undermines the nomination process, as the shortlist has already been drawn up.

Why do Egypt’s international private universities lag in global rankings? And does it even matter? Egypt’s international private universities frequently head up domestic lists of the country’s best post-secondary institutions thanks to international accreditation and a reputation for academic rigor. Attracting more international students is a priority for private universities and the Egyptian government. And new regulations under development by the Higher Education Ministry require any new university to form an academic partnership with an international university. But international private universities don’t generally top Egypt’s university representation in global ranking systems.

What does it mean? That private and international universities in Egypt lag their state-run counterparts? Not necessarily: It comes down to whether you’re ranking research output (where state institutions are ahead) or teaching quality and the total student experience for undergraduates.

Which rankings do we really care about? There is close to a consensus among the sources we spoke to, and online, that the three most important and influential ranking systems out of the many that exist are the QS World University Rankings, the Times Higher Education (THE) World University Rankings, and the Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWO or the Shanghai Ranking).

All but QS places a heavy weight on research, citations, and awards: QS rankings are heavily weighted in favor of academic and employer reputation, with only 20% of the ranking related to citations or research. THE rankings emphasize citations and research, which collectively comprise 60% of the ranking, mostly because research and citations can be quantified — while other criteria like a university’s reputation is much more subjective, THE rankings editor Ellie Bothwell tells Enterprise. ARWU rankings place particular value on the number of alumni and staff who win Nobel Prizes and Fields Medals, as well as research and citations, which altogether count for 90% of an institution’s ranking.

Where exactly do Egypt’s international and private universities rank? In the QS 2020 World University rankings, AUC was the only non-state university to be featured, tied at #395. In the THE 2020 World University rankings, AUC was again the only non-state university to feature, ranked among the group of 801-1000, sharing seventh place in Egypt with Ain Shams, Benha and Tanta universities. In the ARWU 2019 rankings, not a single private Egyptian university featured in its ranking of 1k universities around the world.

Public universities do better across the board. The universities of Aswan, Mansoura, Suez Canal, Beni Suef, Cairo and Kafr El Sheikh all outrank private universities in THE’s World University 2020 rankings. QS, meanwhile, ranks the universities of Cairo, Ain Shams, Alexandria and Assiut within its top 1000, all coming in below AUC but above any other private university. For ARWU it’s the universities of Cairo, Ain Shams, Alexandria, Mansoura and Zagazig that make the top 1000.

Rankings do matter, but it’s important to recognize their limits and view them in context. “No institution wishing to compete globally — or even nationally — can afford to ignore [rankings],” writes Imperial College professor Stephen Curry. But we need to focus less on the sheer numbers and also think about the limitations of what they can measure, he adds.

So what are the main limitations?

Research-heavy ranking systems put less importance on things that matter to business when you’re assessing a university as a potential source of talent. Many crucial aspects of the student experience are not assessed in these rankings, including the applicability of skills to the job market, the quality of facilities and resources, student-to-professor ratios and the availability of professors, multiple sources say. “The factors included in ranking are not enough to measure the quality of education,” says AUC’s Ahmed Tolba, Associate Provost for Strategic Enrollment Management. While research is an important part of academia, Mohamed El Shinnawi, an advisor to Egypt’s Higher Education Minister, says other factors should be considered, pointing to “Student employability after graduation, the curricula and programs, the way students are taught, how graduates adapt to what their local or regional markets need.” QS designs their rankings primarily for students, but other systems are more aimed at university leadership, a 2013 Guardian piece notes.

Rankings are calibrated to reward “the UK and US model of a university.” Newer universities could be at a disadvantage overall because ranking systems tend to prioritize research, citation and awards, which are not the primary focus early in a university’s life cycle, when teaching is the priority. Older institutions are far more likely to have produced Nobel Prize or Fields Medal winners — important criteria for the ARWU rankings, says Mohamed Eid, BUE’s Director of the Internationalisation Office. Wealthier universities can afford to employ more research-focused staff, and lighten their teaching schedules, argues Tolba. And social privilege allows established global universities, with excellent reputations, to continue setting the tone for what is valued, argues Research Fellow Alice Bell. “Our methodology is about ten years old, so probably really caters more for the UK and US model of a university,” says Bothwell. “That’s potentially another reason why some of these universities in Egypt are just lower down in general.”

Even if a student cared about a university’s research, rankings don’t always make available data to corroborate their findings. For example, Aswan University, which tops Egypt’s THE 2020 rankings, basically gets a perfect score for citations, says Bothwell — meaning that its research was cited more often than any other Egyptian university that year. But without the methodology made publicly available, it is difficult to know whether the citations come from a broad spectrum of research papers or a small number of papers that have been frequently cited this year without consulting the raw data — which isn’t publicly available, Bothwell tells us.

But rankings do matter to Egypt’s universities — particularly in attracting talented staff and students, says Yehia Bahei El Din, BUE’s Vice President for Research & Postgraduate Studies. In this sense, they are arguably more important for private universities — which recruit students — than for public ones. And strong research departments are a big pull for prospective staff members, he adds. Rankings can also affect the level of interest from international bodies like Horizon 2020 or the Newton-Mosharafa Fund in providing grants or working with a particular university, says El Shinnawi.

So in marketing themselves, the universities do leverage rankings — but they also seek accreditation, use networks and emphasize their unique value propositions. AUC regularly seeks accreditation from certain carefully selected organizations — such as the National Authority for Quality Assurance and Accreditation of Education (NAQAAE) and the Middle States Commission on Higher Education (MSCHE), a consortium recognized by the US Department of Education, says President Francis Ricciardone. And it taps into its international status as a draw to prospective students. “We’re not Harvard,” says Ricciardone, “but Harvard also isn’t us.” Students don’t just come to AUC to study particular subjects they can specialize in. They come because of the way the university teaches and the experience they will have studying in Egypt, he adds.

So ultimately, where are rankings valuable? They’re important as a framework for comparison, as long as you don’t take them too seriously — or literally. And for Egyptian universities, they can serve as a push to become better and develop their research capacities, says Bahei El Din — though he stresses that rankings are a byproduct of good work, and not an end in themselves.

Possible change to come? Established systems don’t change overnight, but there may also be concrete changes on the horizon. The data officers who design these ranking systems understand the need to more fairly assess teaching and are making efforts to do so, in spite of the challenges that restructuring brings, this THE blog post suggests. The THE would have announced a new methodology for ranking in September 2020, but is delaying the announcement probably by a year because of covid-19, says Bothwell. The new methodology may be more reflective of the global nature of higher education, she says. And new developments — both social challenges and academic disciplines — will make regular review of these evaluation systems essential, as different skills are prioritized, multiple sources predict.

Your top education stories of the week:

- Agreement to develop two int’l schools in O West: Orascom Development Egypt (ODE) has signed an agreement with Nermine Ismail School (NIS) that will see NIS develop two K-12 international schools in the O West compound.

- Fresh online tuition fee payment service: Fintech startups Klickit and Paymob have signed an agreement with GEMS to provide online tuition fee payments for the parents and guardians of over 6k students.

- Finland-backed vocational education: Elsewedy Technical Academy (STA) signed a cooperation agreement with the Finnish Global Educational Solutions (FGES) to implement Finnish vocational education programs in STA technical schools.

- The Education Ministry has guidelines for parents to submit online applications for their year-one children at public and language schools next academic year.

- International school students will be permitted to take end-of-year national curriculum exams from home, according to AMAY.

The Market Yesterday

EGP / USD CBE market average: Buy 16.17 | Sell 16.27

EGP / USD at CIB: Buy 16.17 | Sell 16.27

EGP / USD at NBE: Buy 16.15 | Sell 16.25

EGX30 (Sunday): 11,109 (+4.6%)

Turnover: EGP 1.4 bn (89% above the 90-day average)

EGX 30 year-to-date: -20.4%

THE MARKET ON SUNDAY: The EGX30 ended Sunday’s session up 4.6%. CIB, the index’s heaviest constituent, ended up 5.6%. EGX30’s top performing constituents were Pioneers Holding up 8.6%, EFG Hermes up 8.2%, and TMG Holding up 6.2%. Yesterday’s worst performing stocks were Juhayna down 0.8% and Ibnsina Pharma down 0.3%. The market turnover was EGP 1.4 bn, and regional investors were the sole net sellers.

Foreigners: Net Long | EGP +15.1 mn

Regional: Net Short | EGP -177.2 mn

Domestic: Net Long | EGP +162.1 mn

Retail: 62.0% of total trades | 52.2% of buyers | 71.8% of sellers

Institutions: 38.0% of total trades | 47.8% of buyers | 28.2% of sellers

WTI: USD 39.64 (+0.23%)

Brent: USD 42.63 (+0.78%)

Natural Gas (Nymex, futures prices) USD 1.76 MMBtu, (-1.23%, July 2020 contract)

Gold: USD 1,683.90 / troy ounce (+0.05%)

TASI: 7,267.86 (+0.83%) (YTD: -13.37%)

ADX: 4,405.32 (+2.37%) (YTD: -13.21%)

DFM: 2,133.34 (+4.60%) (YTD: -22.84%)

KSE Premier Market: 5,507.27 (+0.88%)

QE: 9,349.30 (+1.05%) (YTD: -10.32%)

MSM: 3,538.32 (+0.59%) (YTD: -11.12%)

BB: 1,269.85 (-0.27%) (YTD: -21.14%)

Calendar

9-10 June (Tuesday-Wednesday): US Federal Open Market Committee will hold its two-day policy meeting to review the interest rate.

13 June (Saturday): Earliest date on which suspension of international flights to / from Egypt expires.

13 June (Saturday): Earliest date by which restaurants, gyms, nightclubs, museums and archaeological sites will reopen.

22-30 June (Monday-Tuesday): EFG Hermes Virtual Investor Conference.

25 June (Thursday): The CBE’s Monetary Policy Committee will meet to review interest rates.

30 June (Tuesday): Anniversary of the June 2013 protests, national holiday.

12 July (Sunday): North Cairo Court will hold a court session for the international arbitration case filed by Syrian Antrados against Porto Group for USD 176 mn after being pushed back from an initial 17 May court date.

28-29 July (Tuesday-Wednesday): US Federal Open Market Committee will hold its two-day policy meeting to review the interest rate.

30 July-3 August (Thursday-Monday): Eid El Adha (TBC), national holiday.

13 August (Thursday): The CBE’s Monetary Policy Committee will meet to review interest rates.

20 August (Wednesday-Thursday): Islamic New Year (TBC), national holiday.

15-16 September (Tuesday-Wednesday): US Federal Open Market Committee will hold its two-day policy meeting to review the interest rate.

24 September (Thursday): The CBE’s Monetary Policy Committee will meet to review interest rates.

24 September- 2 October (Thursday-Friday): El Gouna Film Festival, El Gouna, Egypt.

6 October (Tuesday): Armed Forces Day, national holiday.

29 October (Thursday): Prophet Mohamed’s birthday (TBC), national holiday.

November: Egypt will host simultaneously the International Capital Market Association’s emerging market, and Africa and Middle East meetings.

4-5 November (Tuesday-Wednesday): US Federal Open Market Committee will hold its two-day policy meeting to review the interest rate.

12 November (Thursday): The CBE’s Monetary Policy Committee will meet to review interest rates.

15-16 December (Tuesday-Wednesday): US Federal Open Market Committee will hold its two-day policy meeting to review the interest rate.

24 December (Thursday): The CBE’s Monetary Policy Committee will meet to review interest rates.

25 December (Friday): Western Christmas.

1 January 2021 (Friday): New Year’s Day, national holiday.

7 January 2021 (Thursday): Coptic Christmas, national holiday.

Enterprise is a daily publication of Enterprise Ventures LLC, an Egyptian limited liability company (commercial register 83594), and a subsidiary of Inktank Communications. Summaries are intended for guidance only and are provided on an as-is basis; kindly refer to the source article in its original language prior to undertaking any action. Neither Enterprise Ventures nor its staff assume any responsibility or liability for the accuracy of the information contained in this publication, whether in the form of summaries or analysis. © 2022 Enterprise Ventures LLC.

Enterprise is available without charge thanks to the generous support of HSBC Egypt (tax ID: 204-901-715), the leading corporate and retail lender in Egypt; EFG Hermes (tax ID: 200-178-385), the leading financial services corporation in frontier emerging markets; SODIC (tax ID: 212-168-002), a leading Egyptian real estate developer; SomaBay (tax ID: 204-903-300), our Red Sea holiday partner; Infinity (tax ID: 474-939-359), the ultimate way to power cities, industries, and homes directly from nature right here in Egypt; CIRA (tax ID: 200-069-608), the leading providers of K-12 and higher level education in Egypt; Orascom Construction (tax ID: 229-988-806), the leading construction and engineering company building infrastructure in Egypt and abroad; Moharram & Partners (tax ID: 616-112-459), the leading public policy and government affairs partner; Palm Hills Developments (tax ID: 432-737-014), a leading developer of commercial and residential properties; Mashreq (tax ID: 204-898-862), the MENA region’s leading homegrown personal and digital bank; Industrial Development Group (IDG) (tax ID:266-965-253), the leading builder of industrial parks in Egypt; Hassan Allam Properties (tax ID: 553-096-567), one of Egypt’s most prominent and leading builders; and Saleh, Barsoum & Abdel Aziz (tax ID: 220-002-827), the leading audit, tax and accounting firm in Egypt.