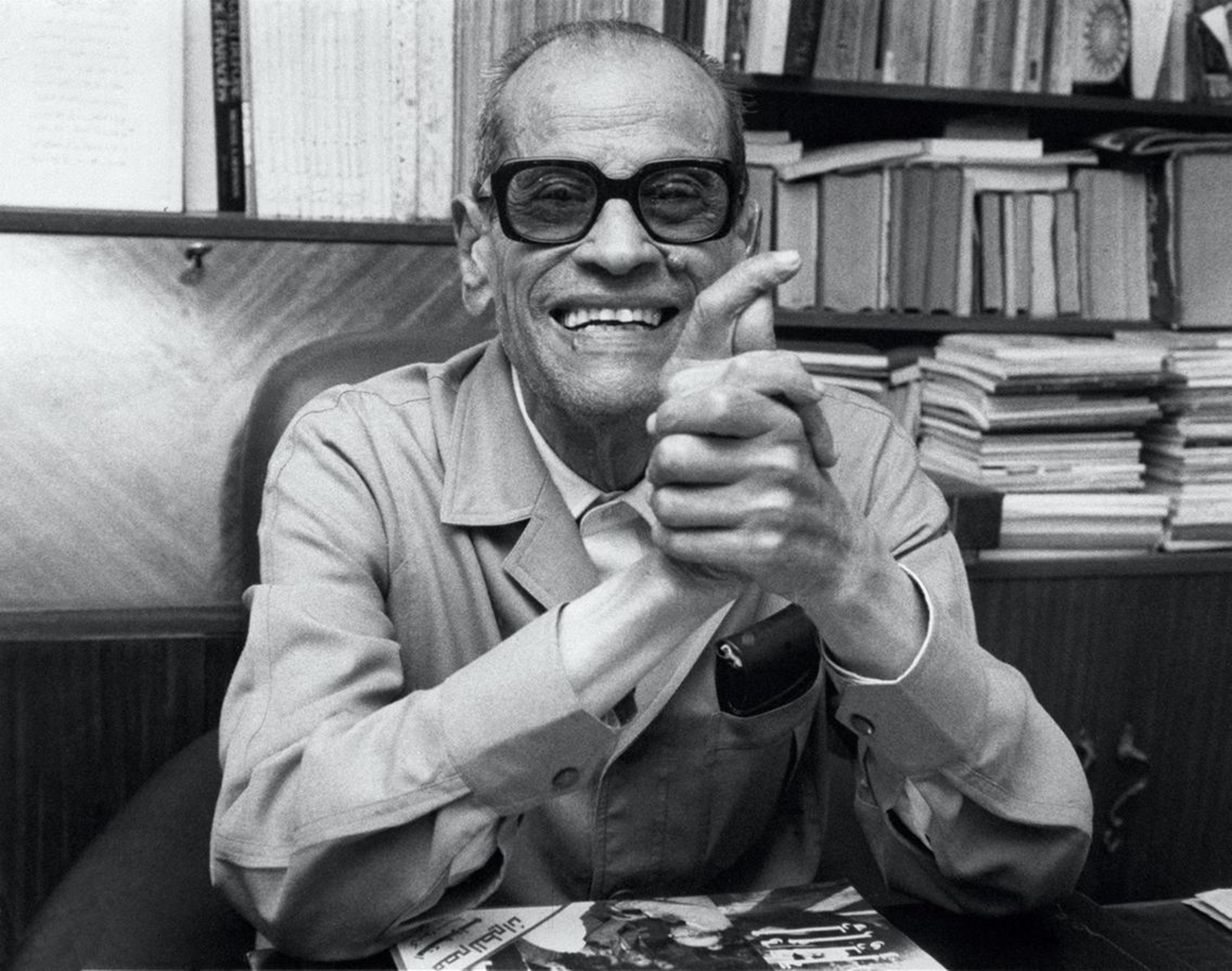

The first Arab author to win a Nobel prize: Naguib Mahfouz’s name is synonymous with old Cairo, whose winding back-alleys he so faithfully captured in his iconic Cairo Trilogy (1956). Widely considered his magnum opus, the trilogy serves as a microcosm of Egyptian society, following a family not dissimilar from Mahfouz’s own across three generations, from the 1919 revolution to WWII. Born in the Al Gamaleya district in 1911, Mahfouz published his first novel in 1939, and would publish forty more along with short story collections, screenplays, stage-plays, and articles throughout his distinguished career.

Father of the Arab novel: A civil servant by profession, Mahfouz served in the Ministry of Religious Endowments, as director of the Censorship Bureau, as consultant to the Ministry of Culture, and as head of the National Film Board. All the while, Mahfouz kept writing, preoccupied with matters perhaps considered unusually existential for a civil servant; time, progress, and the tension between the individual and society, with a strong political undertone running throughout all his novels. His allegorical Children of the Alley (1959, alternately known as Children of Gebelawi) drew the ire of those who objected to the character of Gebelawi symbolizing God, and motivated an assassination attempt in 1994 which left Mahfouz with life-long injuries. The book was banned from publication in Egypt until 2006, the year of Mahfouz’s death aged 94. Widely considered the father of modern Arabic literature, Mahfouz’s portrayal of Cairo — old and new — put the city firmly on the map of world literature, and popularized the now ubiquitous, but originally European, form of the novel in the Arab speaking world. He was awarded the Nobel prize in Literature in 1988, becoming the first Arab author to receive the distinction.

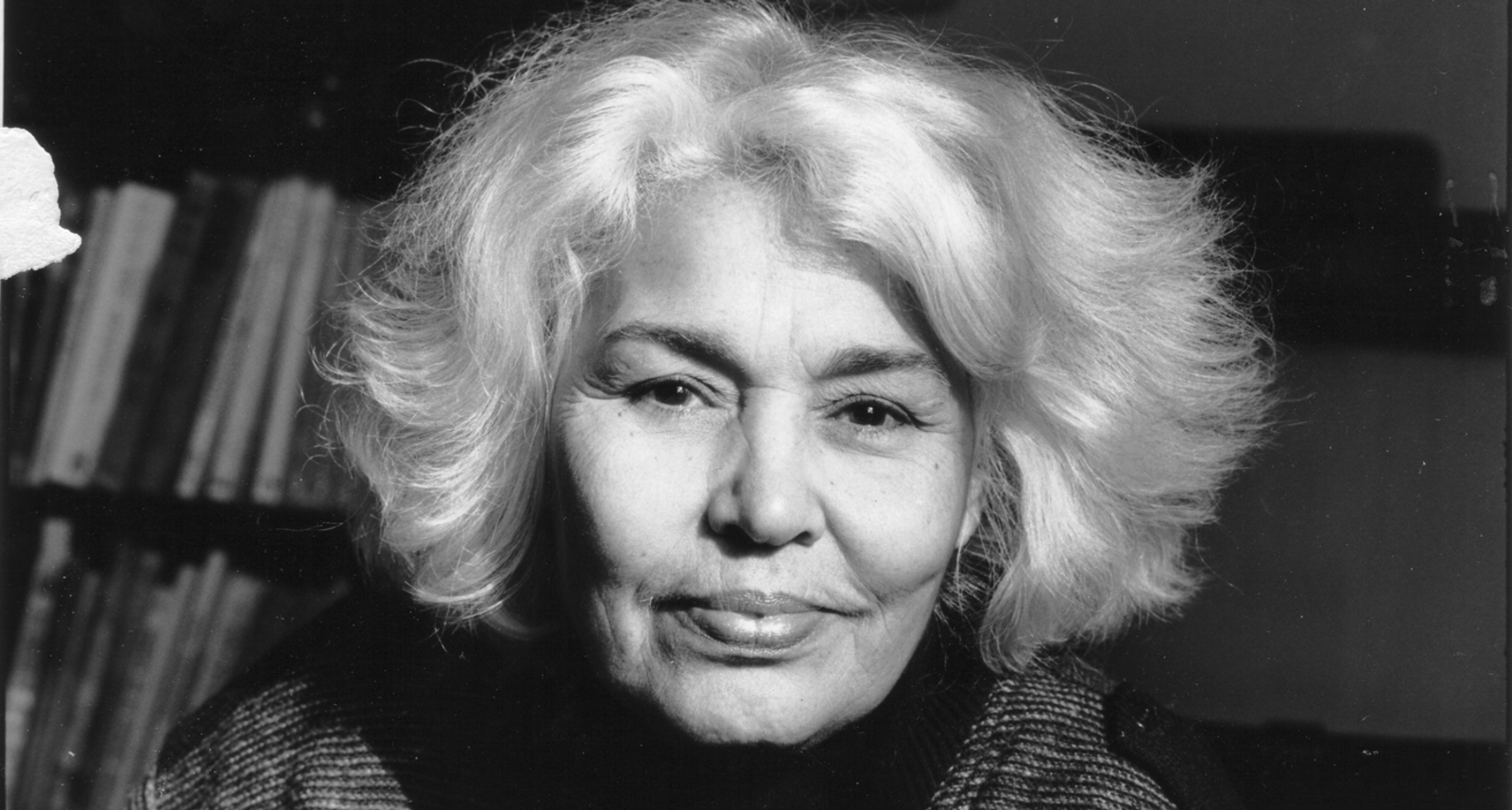

The Simone de Beauvoir of the Arab World: Doctor, psychiatrist, activist, feminist; Nawal El Saadawi wears many hats. Born in Qalyubia in 1931, Saadawi studied medicine and was a practicing doctor throughout most of her career, an experience which allowed her to connect the dots between issues of class, imperialism, and patriarchy which contributed to her female patients’ psychological and physical ailments. Of her more than 50 works, her most famous non-fiction book is perhaps Woman and Sex (1972) — considered a seminal text of second-wave feminism — in which she frankly tackles violence against women’s bodies, particularly female genital mutilation.

A truly radical feminist: Throughout much of her narrative storytelling — which is either loosely based on her own life or overt autobiography — Saadawi addresses women’s health, religion and sexuality head on. Never one to mince words, she was imprisoned for a year in 1981 after criticizing then-president Anwar El Sadat’s policies, an experience that forms the basis of one of her best-known biographical works, Memoirs from the Women’s Prison (1986). Similarly, her most popular novel in translation Woman at Point Zero also takes place in a prison as an inmate recounts the familial abuse and societal oppression that drove her to commit murder. Saadawi’s early candor in addressing women’s issues that had largely been kept in the shadows — as well as her centering of her female characters’ experiences in how her stories were told — paved the way for contemporary feminist writers and thinkers, who are no doubt indebted to Saadawi’s progressive, if not always palatable views. As for her feminist credentials, Saadawi dislikes being compared to Beauvoir, proclaiming in a 2018 interview: “I’m much more radical than her.”