An era that brought life to new ideas and fresh perspectives: A time of significant social and political upheaval, the early 20th century gave rise to some of Egypt’s most iconic figures, who in the 1920s changed the nation in revolutionary — and sometimes controversial — ways.

The woman behind Egypt’s first feminist movement: Huda Shaarawi was one of the most storied and influential figures that helped define the 1920s in Egypt and kick off the country’s first feminist movement. Born in 1879 and homebound until the age of 13 when she was married off to her older cousin, Shaarawi was keenly aware of the vast inequalities that stood between her and her male family members. Though she was born to an affluent family who afforded her a homeschool education, unlike most other women at the time, she remained disenchanted by the fact that she couldn't go to school like her brother.

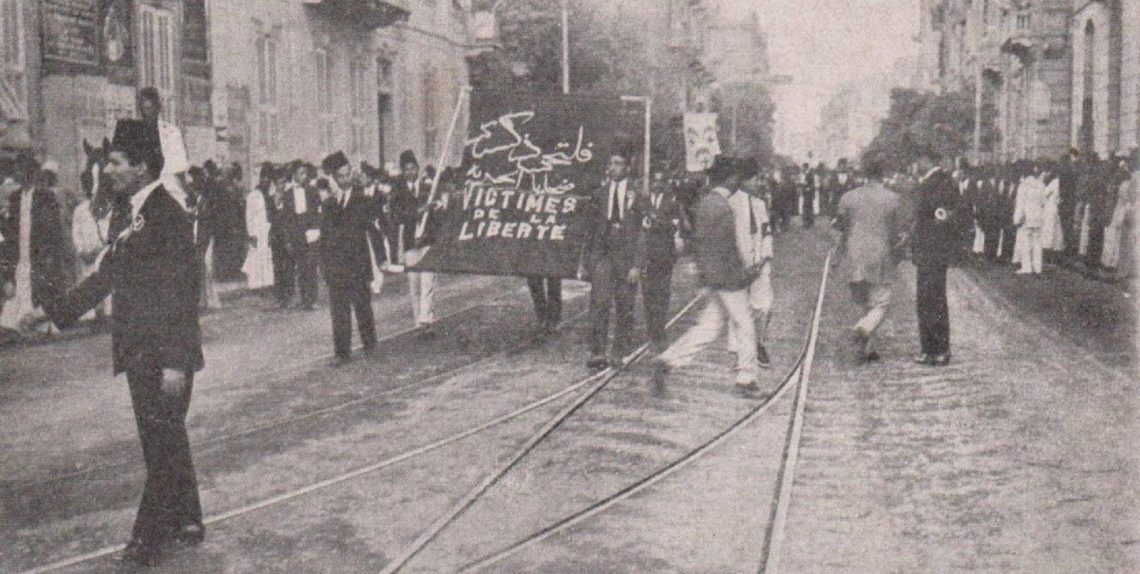

Adult life: Later in her adult life Shaarawi started organizing public lectures for women and became deeply involved in the country’s independence movement. In 1920, Shaarawi was responsible for forming and heading a women’s arm to the Wafd Committee (later the Wafd Party), and a few years later in 1923 Shaarawi founded the Egyptian Feminist Union which campaigned for women’s suffrage, raising the minimum legal age for marriage, and wider access to education for women.

Controversy: The same year Shaarawi had founded the Egyptian Feminist Union she staged one of her most notorius acts of rebellion when she removed her veil outside a train station in Cairo, marking one of the first ever public rejections of the veil in the country.

The nationalist entrepreneur behind the first Egyptian-owned bank: In an era when the Egyptian financial system was dominated by European powers, the idea of setting up an Egyptian bank that was owned by Egyptians would have seemed strangely revolutionary. This is what Egyptian businessman and industrialist Mohamed Talaat Harb set out to do in the early 20th century. First a lawyer then an economist, Talaat Harb went on to become the foremost proponent of setting up a bank owned by Egyptians for Egyptians.

Enter Banque Misr: A staunch nationalist, Talaat Harb was driven by his belief that economic development was the key to Egypt securing independence from British rule. “We need a genuine Egyptian bank operating along with the existing banks, to extend a helping hand to Egyptians, encourage them to venture into industry and trade, urging them to save and make use of financial activities,” he wrote in a book in 1911. Following the 1919 uprising, he persuaded 126 Egyptians to contribute capital to a new bank, which would become the first financial institution to be controlled by Egyptians and to have Arabic as its primary language. Working alongside his Egyptian-Jewish partner, Joseph Cattaui, Talaat Harb opened the doors of Banque Misr in 1920.

The Arab world’s first woman journalist: Lebanese born Rose Al Yusuf is responsible for bringing into existence the now state-owned literary magazine Rose Al Yusuf and an icon of Egypt’s independence movement in the early 20s. Yusuf started out as a child actor in the early 20th century but later decided to apply for a magazine publishing license, despite having very little funds or experience.

The Rose Al Yusuf magazine started out as an art publication, but quickly turned political, adopting an explicitly anti-colonial tone and writing openly about taboo topics. The vocal support for independence attracted the ire of the British authorities and the palace, who canceled her license and arrested her. During this time, Yusuf continued publishing under a different name, The Shout, until Al Yusuf was eventually allowed to resume publishing under its original name.