The case for investing in EM economies has “rarely been weaker,” argues the FT

With EM economies facing slowing growth, soaring debt, and imminent US interest rate hikes, the case for investing in them has “rarely been weaker,” argues Jonathan Wheatley in the Financial Times. Amid the ongoing covid-19 pandemic, many EM economies have accrued high levels of debt, which they relied on to finance fiscal spending and support economic activity. Now faced with rising inflation and slowdowns in global trade, many are seeing sluggish GDP growth. Amid an already high-risk environment, the biggest risk of all is set to come from hikes in US interest rates. All of this undermines the key value proposition for EM investment: Without high growth, investors are left with many risks and few potential gains.

Rising US interest rates are expected to hit EMs hard: Major investment banks anticipate a cumulative hike in US interest rates of 125-175 bps in 2022, starting in March, Reuters reported recently. This tightening will reduce the appeal of investing in EM assets, Wheatley says. EM stocks and bonds saw outflows of some USD 7.7 bn in January, accompanying a sharp rise in 10-year US Treasury bond yields, representing “a pre-tightening of financial conditions well ahead of any official interest rate increases,” according to one analyst. With rate hikes likely to strengthen the USD, the cost of servicing existing USD-denominated debt will likely increase, dampening foreign investment and hindering trade, Wheatley adds.

While red-hot inflation and slowing global trade are curbing EM outputs: Inflation has become a global problem, with 15 of the 34 countries classified as advanced economies by the IMF’s World Economic Outlook, and 78 out of 109 countries classified as emerging or developing economies, seeing annual inflation rates above 5% through December 2021, according to a recent World Bank blog post. The global inflation shock has forced “abrupt” EM policy interest rate hikes, weighing on growth, Fitch notes. And global trade, traditionally a key source of output growth for EMs, is set to slow sharply in 2022 and 2023, as pent-up demand lessens, according to the World Bank.

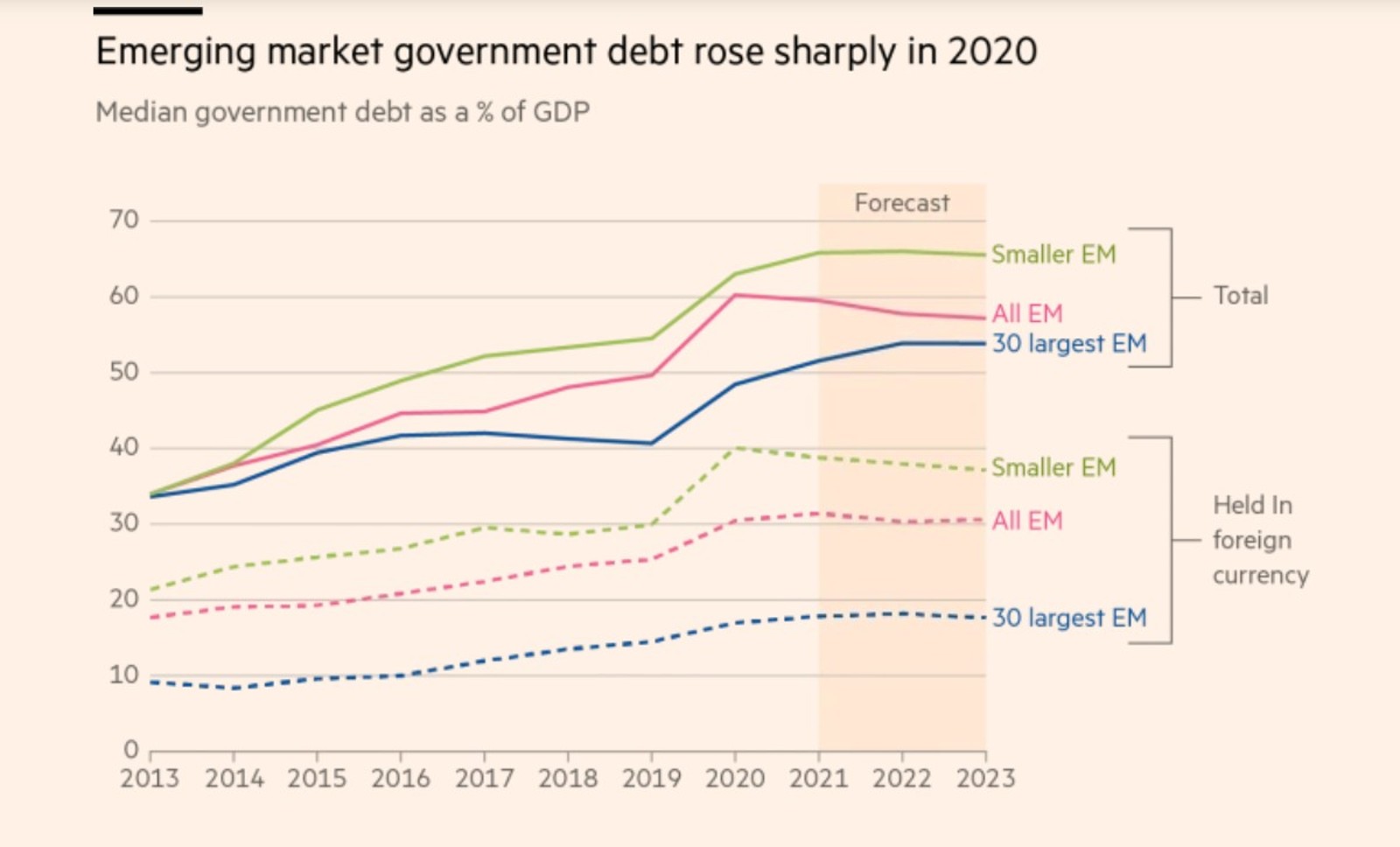

As, of course, are high levels of debt: EM fiscal spending to mitigate the worst effects of the pandemic, by stimulating activity and supporting businesses, was largely financed by debt, Wheatley notes. The median level of government debt to GDP in 80 EMs rose to over 60% in 2020 to just under 50% in 2019, according to Fitch data. Though this is forecast to remain steady or even slightly decrease through 2023, it still represents “a huge increase for a single year,” he says.

It’s all weighing on EM GDP growth: EM growth is expected to fall to 4.6% in 2022 and 4.4% in 2023, from 6.3% in 2021, according to World Bank data. Though advanced economies will also see declining growth, they will all still have achieved full output recovery by 2023, the World Bank anticipates. But overall EM output will remain 4% below its pre-pandemic trend by 2023, with some of the most vulnerable economies seeing growth that’s 7.5-8.5% below pre-pandemic trends.

Higher US interest rates and a strengthening USD are particularly problematic for smaller EM economies: The 50 smaller economies rated by Fitch will be buffeted by these headwinds more than the 30 largest because their debt levels are higher and their share of foreign currency debt is much greater, Wheatley notes. These economies could face “a legacy of fiscal difficulties that take years to resolve.”

A host of “fragile” EMs are less able to withstand shocks, while several have already defaulted, since the pandemic began: Ghana, El Salvador, and Tunisia — along with Ukraine, particularly now with the Russian invasion underway — are much less likely to be able to manage shocks that could hit them this year, says Fitch’s head of global sovereign research. Argentina, Belize, Ecuador, Lebanon, Suriname and Zambia have already defaulted during the pandemic.

And many saw their credit conditions deteriorate in 2020: Fitch issued a record 45 sovereign downgrades in 2020, hitting 27 of the EMs it issues ratings for.

It all paints a bleak picture, but there are still reasons for optimism: In some important ways, EMs are better placed than they were in the past to withstand shocks like exchange rate volatility and see-sawing risk appetite from international investors. For one, EMs are as a whole running a current account surplus, with some large economies like Brazil, South Africa, and India having substantial FX reserves and deep local capital markets. And so many investors retreated from EM stocks and bonds that a further sell-off is unlikely, and prices have even decreased enough to entice some foreign investors back, Wheatley notes.

Fixed-income investors may also be drawn by EMs with rising interest rates and declining inflation: Some EMs, including Brazil, started raising their interest rates nearly a year ago, with Brazil’s policy rate currently standing at 10.75%, up from 2% in March 2021. It’s expecting to see inflation decline to 5.5% towards the end of the year, from over 10% currently. High interest rates and relatively low inflation can be a giant magnet for investors, with high yields available on hard currency bonds already offering “tempting annual returns in the high single digits.”

Higher EM interest rates could ultimately revive the carry trade, resulting in a boom in local-currency bonds, Wheatley concludes.

In a precarious EM landscape, Egypt has been bucking many of the downward risk trends: Egypt is seeing strong economic growth, expected to come in at 6.2-6.5% in FY2021-2022, up from 3.3% in FY2020-2021. Though inflation is high, with urban inflation rising to 7.3% last month from 5.9% in December, it remains within the Central Bank of Egypt’s target range of 7% (±2%) by 4Q2022. And our interest rate is currently the world’s highest after adjusting for inflation, we noted last month. Egypt’s local bonds were the world’s second-best performing worldwide last year, with returns reaching 13%, according to Bloomberg data. Local EM debt saw an average loss of 1.2%. Egypt’s carry trade has long been a draw for foreign investors.

Analysts and fund managers are bullish on Egyptian debt, expecting double-digit returns this year, bolstered by Egypt rejoining JPMorgan’s emerging bond index in January.

Ultimately, our position seems strong. But it looks like a rate hike may be necessary in 2022 for it to remain so: Though the CBE left interest rates on hold for the tenth consecutive meeting earlier this month, expectations for a 2022 rate hike are increasing, we noted. Several analysts are forecasting a 100bps hike through the year, as the central bank looks to protect the lucrative carry trade in the midst of rising global interest rates, which undermine EM inflows.