Women all over the world still face laws that bar full economic participation — but here in Egypt, things are improving

A new World Bank report serves up hard facts about laws that continue to bar women’s economic participation. There are about as many ways to address gender inequality as there are women in this world (some 3.8 bn). If your social media feeds are anything like ours, you’ll know that squeezing them all into one International Women’s Day can result in a cacophony of opinion that leaves us even less sure of where to go from here. The World Bank’s Women, Business and the Law 2022 (pdf) report cuts through the noise. The survey of 190 economies aims to answer one key question: To what extent to discriminatory laws continue to prevent women from “fully and equally contributing” to their economies?

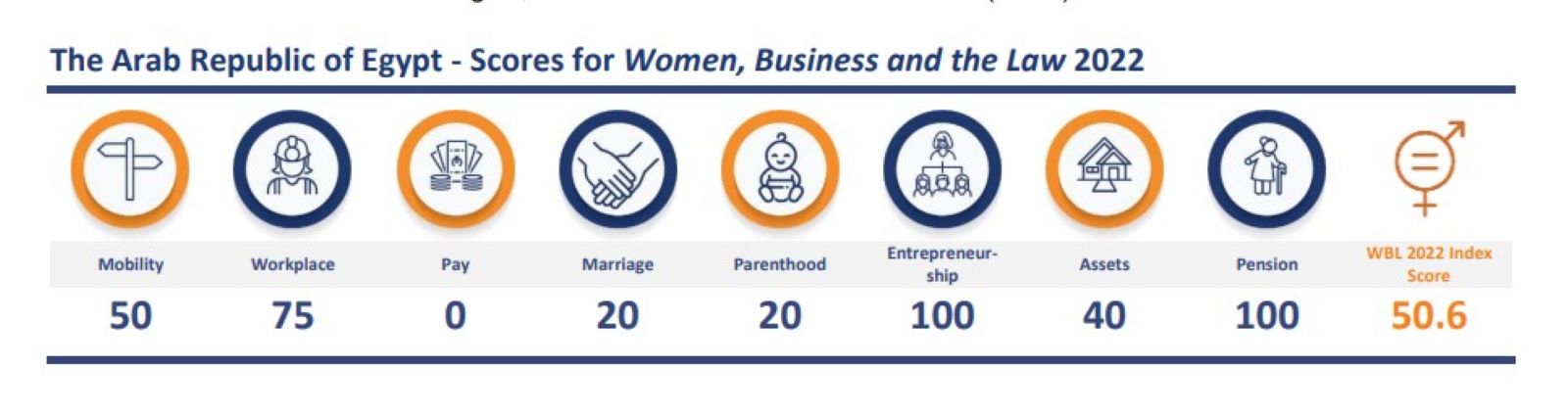

Newsflash: Most women still don’t enjoy equality under laws that impact economic prospects. The report gives countries a mark out of 100 for parity between men and women in eight key areas “structured around the life cycle of a working woman”: mobility, workplace, pay, marriage, parenthood, entrepreneurship, assets, and pensions. The global average score was 76.5 — up just half a point on last year’s report. Only 12 countries got a perfect score on all fronts.That means the average woman enjoys only three-quarters of the rights under law of a man in the areas measured, while some 2.4 bn women of working age worldwide live in countries where the law does not grant them equal economic rights.

Here at home, we’re making progress — but there’s still a long way to go. Our score improved for the first time since 2016, rising by a significant 5.6 percentage points to record 50.6. Nevertheless, that still means Egyptian women enjoy only about half the rights of men in areas that impact economic participation. The report ranks us 171st out of the 190 countries assessed, and below the MENA average of 53.0 — which itself was the lowest score of any region.

What’s improved for Egyptian women? Our score on marriage laws went from a dismal 0 to 20, after we introduced our first-ever legislation (pdf) specifically addressing domestic violence. Meanwhile, a central bank circular (pdf) last year “made access to credit easier for women by prohibiting gender-based discrimination in financial services,” the report’s Egypt snapshot (pdf) says, pushing our entrepeneurship score from 80 to a perfect 100.

Where we continue to do well: We’re still doing a good job on workplace rights, where our score of 75 is unchanged thanks to legislation in place prohibiting workplace [redacted] harassment and discrimination in employment based on gender. Our perfect score on pensions also remains in place, due to men and women getting the same pension benefits and having the same retirement age.

And where could we be a whole lot better: Egypt’s worst area is pay, where we still score a big fat zero thanks to a lack of laws mandating equal pay for equal work, as well as restrictions on women working in the same way as men at night, in jobs deemed dangerous, and in the industrial sector — a state of affairs the report says we “may want to consider” changing.

There’s also room for improvement in laws affecting marriage, parenthood, mobility, and assets. Divorce and remarriage rights remain unequal, sufficient maternity and parental leave is yet to be enshrined in law, women still face restrictions on movement (including unequal procedures to obtain a passport), and equal inheritance rights remain elusive.

Expect to see Egypt make further progress in next year’s report: The draft Labor Act, which got the greenlight from the Senate in February, will increase paid maternity leave to four months from the current three months. That should tick off a key measure in the report’s parenthood gauge, which gives points for countries that mandate paid leave for mothers of at least 14 weeks.

Elsewhere in the region: MENA came in last place of the seven regions surveyed — but it was also the report’s best improver, with countries in the region enacting ten of the 39 law reforms that improved women’s economic rights last year. Some 25% of MENA economies implemented at least one reform, pushing the regional score up by 1.5 points. That said, women in MENA continue to face some of the most entrenched barriers to economic participation, with 11 countries in the region placing in the bottom 20 worldwide. Coming in very last place globally was the West Bank and Gaza, with a score of 26.3, while Yemen and Qatar also came in with scores under 30.

On the bright side: We may experience more gender equality in practice than is enshrined by law. This year’s report newly surveys local experts on gender inequalities, in an attempt to measure the gap between the letter of the law and the way it’s implemented in practice. MENA “is the only region where expert opinions indicated more gender equality in practice than the index implies,” with Egypt and Oman registering the largest positive difference.

Why does this matter? Apart from being plain wrong, persistent gender inequality has a pervasive economic impact. Globally, the difference between men’s and women’s total expected lifetime earnings is USD 172.3 tn, or twice the world GDP. The report’s argument is that only by supporting women to work, own assets and businesses, make their own decisions about marriage and mobility, and access childcare, can we hope to produce truly resilient economies.