Food security is becoming more challenging with soaring global inflation

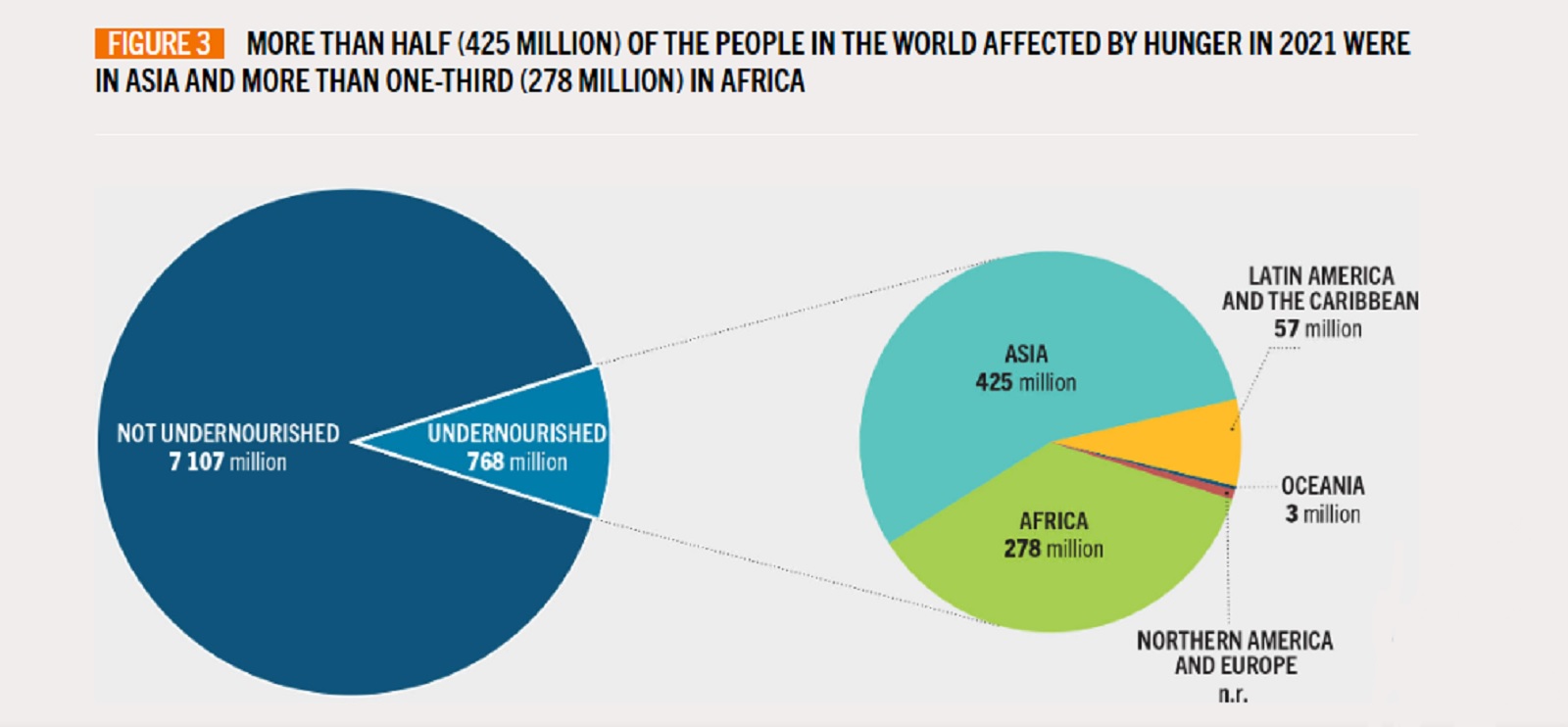

World hunger worsened in 2021 and we’re falling way behind on our goal to eliminate it by the end of the decade. The number of people affected by hunger globally rose to some 828 mn in 2021, clocking an increase of about 46 mn people since 2020 and 150 mn since the outbreak of covid-19, according to a report from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) on the state of food security and nutrition. Worsening economic conditions around the globe and lost income resulting from the global disruptions caused by covid-19 and the war in Ukraine has made access to more nutritious food more difficult (and more expensive) than at any time in the previous seven years — for many middle and lower middle income countries around the world the situation is even worse.

Some 670 mn people will still be affected by hunger by 2030, the report predicts. By the end of the decade, some 8% of the global population will still be coping with some form of hunger, even if a global economic recovery gets underway, the report explains. “With eight years remaining to end hunger [before the UN Sustainable Development Goal deadline], food insecurity and all forms of malnutrition the world is moving in the wrong direction,” the report says.

The challenge of food security isn't equally shared and some countries will bear a much heavier burden than others: Despite a sharp rise in moderate to severe food insecurity globally in 2020, those same levels remained mostly stable throughout 2021. Severe food insecurity, however, grew 2.4 percentage points from 2019 to 2021 to 11.7% of the global population, indicating that those already struggling with food security face an increasingly worsening situation.

Much of that struggle is concentrated in Africa: The number of people affected by hunger in Africa is expected to substantially grow from almost 280 mn in 2021 to some 310.7 mn people by 2030, according to the report. In the year preceding the report’s publication last month, moderate or severe food insecurity increased most sharply in Africa, which was already the region home to the highest levels of moderate and severe food insecurity, reaching 34% in 2021 up from 30% in 2020. During this same period, the global average of moderate or severe food insecurity fell to 29.3% from 29.5%.

The pandemic and the war in Ukraine have had a particularly harsh effect on food security globally: The outbreak of covid-19 alone has already been estimated to be responsible for leaving 78 mn more people affected by hunger by 2030 than in a scenario where the pandemic hadn’t taken place, the report finds. The war in Ukraine, which hadn’t yet been accounted for in the FAO’s data for the 2022 edition of their report will likely “have multiple implications for global agricultural markets through the channels of trade, production and prices, casting a shadow over the state of food security and nutrition for many countries in the near future,” the report said.

But the bigger picture is that there are a bunch of reasons why we’re doing so terribly on eliminating hunger: The combination of extreme weather events stemming from climate change, armed conflict, economic crises and pre-existing inequalities are the main drivers of food insecurity globally, the report explains.

In low and middle income countries who rely on imports for a good chunk of their calories, the situation is tenuous: Net food importers like Egypt — which, for example, relied on Russia and Ukraine for over 80% of its imported wheat — have in the past several been feeling the bite of the war. The slowdown in grain shipments and skyrocketing prices have forced Egypt to find new import markets and rely more on local farming output to ensure our supplies of the staple commodity were not disrupted. The consequence of the disruption has been brutal for state budgets which saw an extra EGP 15 bn added to the country’s import bill in the last quarter of FY2021-2022 and could see an extra USD 10.2 bn in the next fiscal year. But still, despite the government’s attempts to shoulder a portion of these costs, people have been increasingly squeezed by the rising costs of food.

Even with a dip in food prices, inflation is still weighing on us: Although food prices fell for the fourth consecutive month in July as the costs of grains and vegetable oil dropped, food prices remain incredibly high by historical standards. July’s reading was the sixth highest since the FAO index began in 1990 and is 13% higher than a year earlier in July 2021.

There are still pathways to changing course on this trajectory: ”In low-income countries but also in some lower-middle-income countries where agriculture is key for the economy, jobs and livelihoods, governments need to increase and prioritize expenditure for the provision of services that support food and agriculture more collectively,” the report says. Part of that means adjusting fiscal subsidies so that they target consumers rather than producers, the report explains. Instituting border measures and market price controls as well as expanding public support for agriculture globally would also help make healthy diets more affordable worldwide.