Developing countries could be in for a 1980’s-style debt crisis

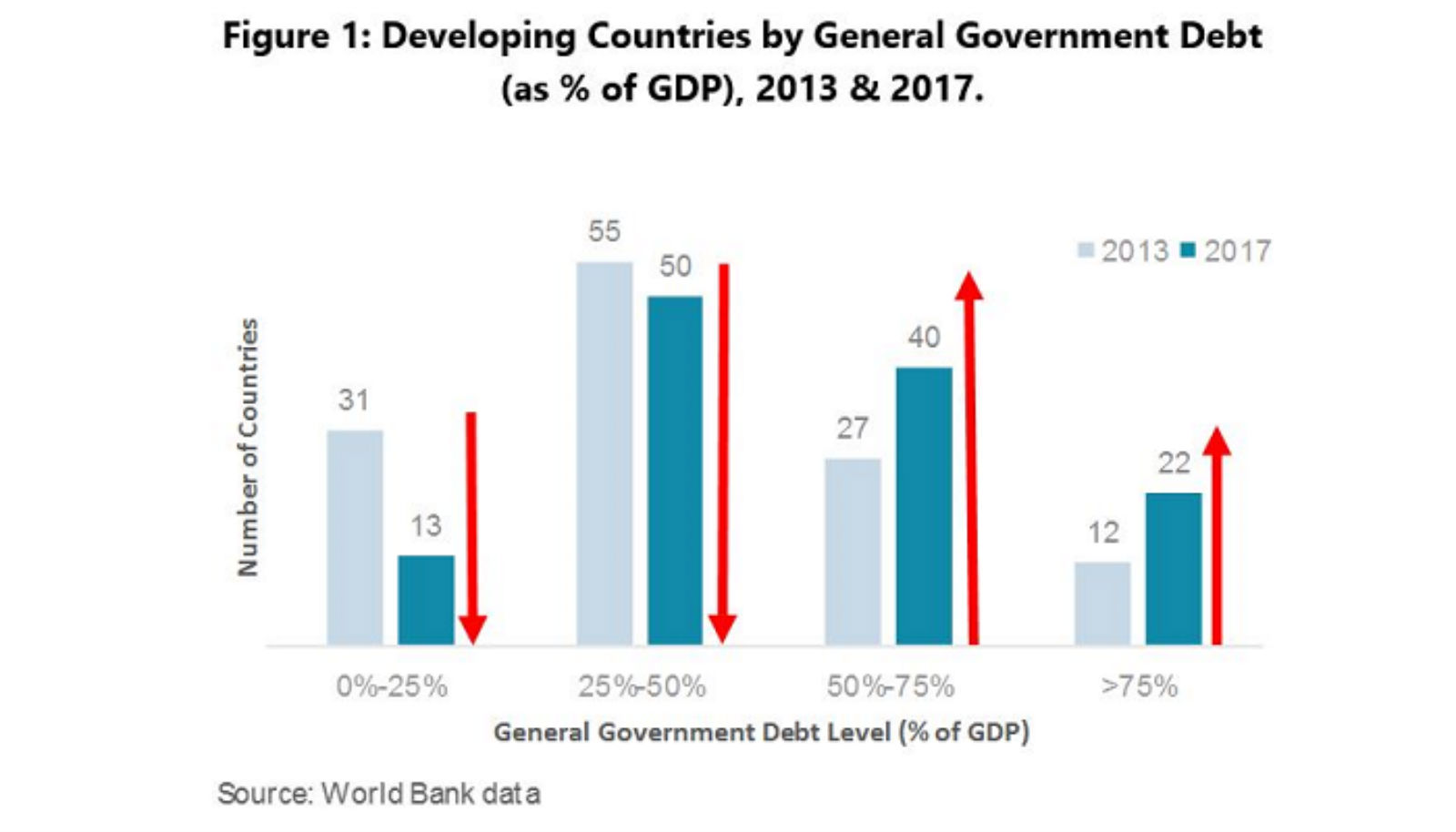

Developing countries could be in for a 21st century debt crisis, senior executives from policy advisory firm Dalberg write for the Financial Times’ BeyondBrics blog. More than 100 emerging markets witnessed government debt-to-GDP ratio hikes between 2013-17, and debt-servicing burdens have risen enough to draw parallels with the lead-up to the 1980’s debt crisis. At the time, Zambia, Cameroon and Malawi had to spend some 40% of state revenue to service debt, diverting much-needed funds away from social development and healthcare.

The bulk of new debt comes from the external loan agreements of 16 low and lower-middle-income countries. China — the single largest bilateral, country-to-country, creditor — loaned out 44% of the funds, while the World Bank, and other large multilateral lenders including the IMF, accounted for 35%. China has previously come under fire for its Belt and Road Initiative, which some countries have criticized as the “new version of colonialism” that has lured countries into debt traps. Loans to lower-income nations caused the IMF to rate in 2017 public debt as “unsustainable” or “at high risk of unsustainability” in 32 countries, as opposed to only 15 in 2013.

Egypt was the only country to improve its public debt risk rating between 2013 and 2017, according to IMF ratings cited by the otherwise gloom-ridden piece. The authors provided no explanation for Egypt standing out, despite government debt increasing in virtually every other developing economy (and our own debt-to-GDP ratio reaching 98%). This could have been a base effect from the aftermath of the 2011 revolution, and maybe because we were the only Arab Spring country to apply for a loan as large as USD 12 bn from the very institution doing the risk rating. While borrowing for development is an effort toward the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, the FT piece says, equal efforts should be made to improve the sustainability of the financing itself.