How we’re preserving calligraphy

Fears abound that technology and digital culture will efface calligraphy: It’s one of our most ancient and enduring forms of self-expression, whether decorating artwork, adorning mosques, or carrying messages of social change. But in the present day, the position of Arabic calligraphy in our lives is far from straightforward as it fights to stay relevant. Specialized calligraphy institutes like the 1928-founded Khalil Agha school have struggled to survive amid a lack of job prospects for learners and waning interest.

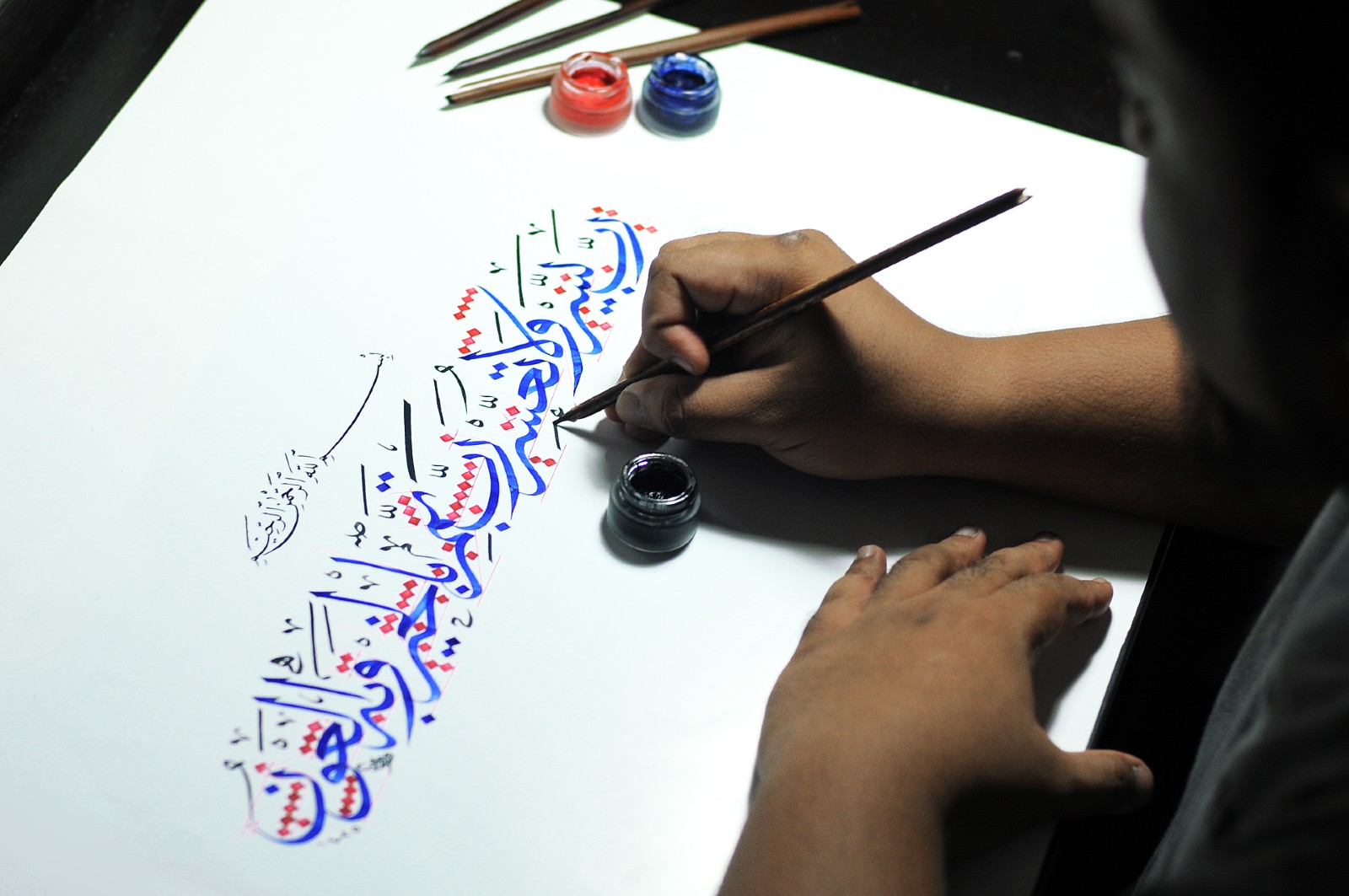

These fears have prompted a revival movement of sorts: Egypt was among sixteen Arab countries to register Arabic calligraphy with UNESCO as intangible heritage in 2020. Last year was designated The Year of Arabic Calligraphy by Saudi Arabia — later extended into 2021 — as a means of preserving and supporting the art form. And initiatives spearheaded by artists, including writers and graphic designers, seek to highlight its cultural value.

Arabic calligraphy is as old as Islamic civilization itself: Calligraphy emerged with the first written version of the Quran in 664-656, and developed into two major styles: Kufic and Naskh. Architectural calligraphic friezes were especially popular in Egypt in the Fatimid and Ayyubid dynasties. And the 1922 founding of the Royal School of Calligraphy in Cairo marked a key moment in the history of Arabic calligraphy, believes one graphic designer who specializes in the art form.

Now it lives on as inspiration for modern-day designers: With its focus on geometry, harmony and proportion, Arabic calligraphy has influenced designers in Egypt and throughout the Arab world for as long as Islamic civilization has existed, believes university art professor Dalia Attieh (pdf). It is a key element in regional interior design as it reinforces the sense of Arabic culture and religion, according to architecture blog Comelite Arch. Egyptian contemporary jewelry designer Azza Fahmy famously draws inspiration from calligraphy, with particular collections inspired by notable poets. Egypt-based Lebanese light designer Nadim Spiridon integrates motifs from Arabic calligraphy into his work. And for architectural designer Nedal Badr, consciously raising awareness of Arabic calligraphy is a key part of what he does, he noted during the 2019 Paris Design Week.

…And in street art: “Khatt: Egypt's Calligraphic Landscape” shows the ubiquity of calligraphy as art and a way of capturing what’s happening in the minds and daily lives of Egyptians, Scene Arabia notes. The book documents khatt — Arabic street calligraphy — on trucks, boats, cinemas, shops, and in Hajj paintings. Efforts to keep Arabic calligraphy alive include Calligraffiti — an art form combining calligraphy, typography, and graffiti — which has evolved into a global movement, and the Kufigraffiti movement, launched by a team of Egyptian graphic designers in 2018 (watch, runtime: 02:12). Street art is now one of the most popular contemporary forms of calligraphy, with artists like El Qaqa and El Seed (he of the famous Garbage City mural) creating famous works in public spaces.

WANT TO LEARN CALLIGRAPHY? AUC New Cairo is set to offer a two-week course for EGP 3.5k from 4-15 July, which may be the best bet for serious learners. Heliopolis Public Library offers workshops for children every Friday. Art Cafe Egypt was offering courses as of September 2020. Azza Fahmy Studio has previously offered 5-day workshops for EGP 4k or USD 300, and the Galileo Art Center has also offered standalone courses. If you’re willing and able to go further afield, Ahlan language school offers 10 or 20-hour courses in Amman. And two good online options for self-study are this course by Udemy that works with the Thuluth Script, and this by Arabic Calligraphy that incorporates six scripts, including Kufic, Naskh and Thuluth.