Why we now need to be talking more about EMs

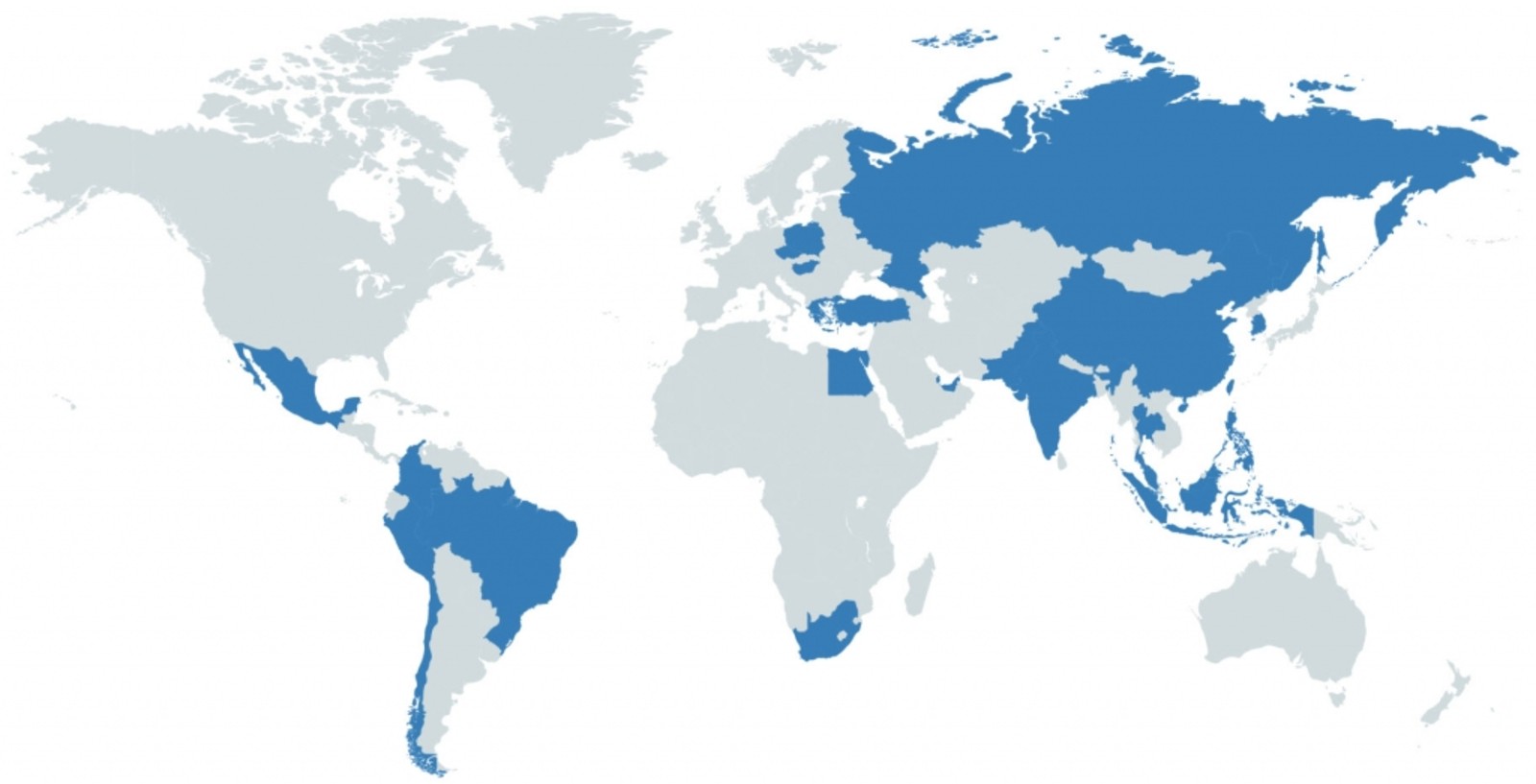

Why we now need to be talking more about EMs: Middle-income economies that stand halfway between the world’s richest and poorest “are uniquely vulnerable in the pandemic.” Despite this, those countries have largely been absent from the global narrative about the extraordinary steps needed to shield the global economy from the fallout, the Financial Times’ (paywall) editorial board writes in an op-ed.

Emerging economies have been tapping local debt markets or counting on central bank reserves, but unlike developed countries, they can’t depend on bn-USD stimulus programs and, unlike the poorest countries, aren’t in line for debt relief. This is made worse given the high debt levels, shaky healthcare systems, economic stagnation and serious inequality that characterized many EMs going into the crisis.

The risks are worthy of our attention: EM aren’t just shaky economies, they’re also often clogged with political unrest. The fallout from the outbreak, thus, not only threatens pushing mns into poverty but has the potential to give way to waves of internal unrest. And while many EM are still able to access international capital markets, “the calm is deceptive,” the FT writes. “As virus-induced recessions hit emerging markets with full force, budget deficits will blow out, triggering a wave of downgrades by ratings agencies and scaring away investors.”

One solution is to increase the IMF’s firepower: The IMF has so far lent out USD 25 bn to vulnerable countries, but this is far from the USD 2.5 tn in financial needs the fund has estimated for EMs. Rich countries have been considering making their IMF special drawing rights (SDRs) available to hard-hit countries including island nations in the Pacific or the Caribbean. This move could set a precedent, but much more should be done to increase the fund’s capacity as a lender of last resort.