Somalia’s central bank-less, mostly fake paper currency

Possibly the strangest monetary phenomenon in the world: Somalia, quite possibly, has the world’s strangest monetary phenomenon, JP Konig argues on his blog. Konig calls its currency, the Somali shilling, an “orphaned” one as it exists without a central bank. Although the Central Bank of Somalia and the national government ceased to exist when a civil war broke out in 1991, Somali shilling banknotes continued to be used as money by Somalis. On top of the existing banknotes in circulation Somalis also accepted a steady stream of counterfeits that circulated with the old official currency. This is not new news. William J Luther writes “Somalis found it profitable to contract with foreign printers and import forgeries. The exchange value of the largest denomination Somali shillings note fell from [USD] 0.30 in 1991 to [USD] 0.03 in 2008. However, the purchasing power eventually stabilized at the cost of producing additional notes.”

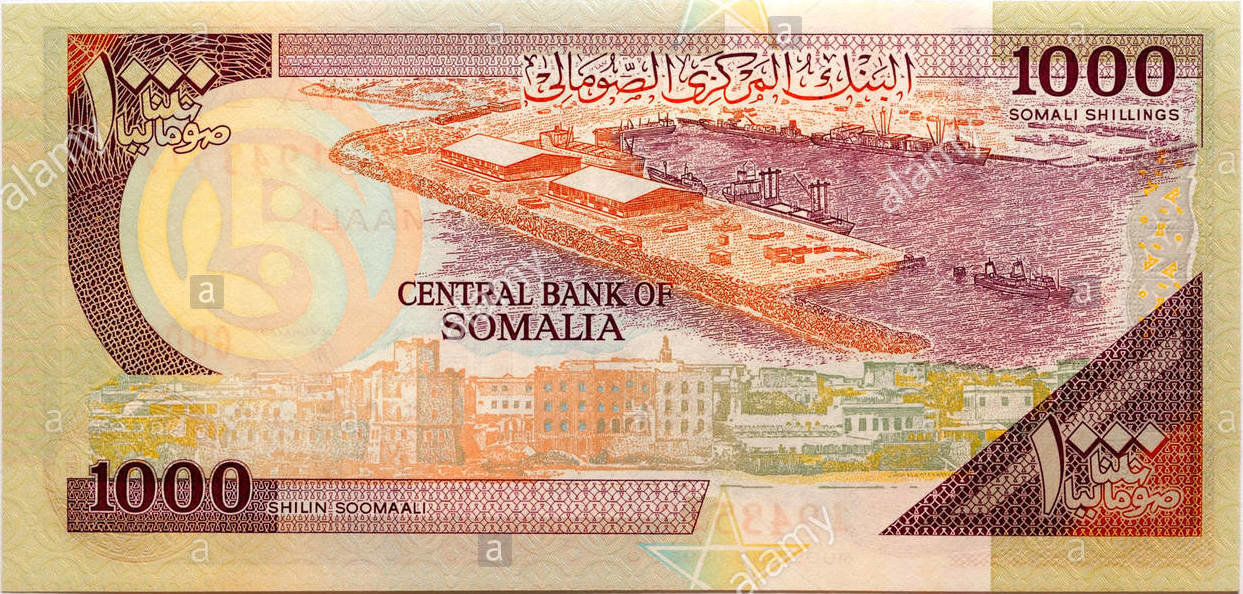

Konig says the story is worth revisiting again now because Somalia’s newly restored central bank, assisted by the IMF, is on the verge of reprinting printing banknotes after a quarter century absence. The more striking part is that the system, which ran without a central bank and a large proportion of counterfeit currency worked. “Old legitimate 1000 shilling notes and newer counterfeit 1000 notes are worth about 4 U.S. cents each. Both types of shillings are fungible—or, put differently, they are accepted interchangeably in trade, despite the fact that it is easy to tell fakes apart from genuine notes. This is an odd thing for non-Somalis to get our heads around since for most of us, an obvious counterfeit is pretty much worthless. The exchange rate between [USD] and Somali shillings is a floating one that is determined by the cost of printing new fake 1000 notes. For instance, if a would-be counterfeiter can find a currency printer, say in Switzerland, that will produce a decent knock off and ship it to Somalia for 2.5 U.S. cents each (which includes the cost of paper and ink), then notes will flood into Somalia until their purchasing power falls from 4 to 2.5 U.S. cents… at which point counterfeiting is no longer profitable and the price level stabilizes.”

A big problem facing the central bank and IMF now is what to do with the old, counterfeit notes already in circulation. “According to the IMF mission chief Mohammed Elhage, the IMF is in the midst of trying to determine at what price it will convert old notes for new official ones. So rather than repudiating counterfeits, the normal route taken by central bankers, the CBS will buy them up and cancel them.”

Practicalities aside, the situation in Somalia raises a fundamental economic question that has never been satisfactorily answered, Konig argues; why is fiat money valuable? “One famous answer to the riddle of fiat money is that governments use force to ensure that fiat money is valued. But this can’t be the case in Somalia: it hasn’t had a government since 1991, yet shillings continue to be accepted. A second answer is that once money is valued—say because it a central bank has been pegged to an existing store of value like gold—then once the central bank disappears and the anchor is lost, those orphaned notes will continue to have value by dint of pure inertia and custom. This theory certainly seems to fit Somalia’s experience. The last theory is that when a central bank is destroyed, the money it issues will quickly become worthless… unless citizens expect a future central bank to emerge and reclaim the orphaned currency as its own.” Koning, who believes that “introducing a new paper currency is a bad idea,” says the second and third theories seem to fit the data.