- Edita has its sugar back. (Speed Round)

- CBE Corridor Rate hikes make a bad situation worse. (A Contrarian View)

- State wheat buyer makes biggest purchase in 2 years ahead of devaluation. (Speed Round)

- EGP hits a fresh low, but 12-month NDFs are at 13.75 to the greenback. (Speed Round)

- Eastern Tobacco raises specter of FX-driven production shutdown, then backtracks. (Speed Round)

- Cairo is Uber’s fastest-growing city in Europe, Middle East and Africa. (Speed Round)

- Apex International Energy opens Cairo and Houston, gets backing from Warburg Pincus. (Speed Round)

- A Cairo bookstore that welcomes your screams. (Worth Watching)

- By the Numbers + Devaluation in the Driver Seat

Thursday, 27 October 2016

Edita gets is sugar back

TL;DR

What We’re Tracking Today

Are you a runner? SODIC’s annual Charity Run in collaboration with Cairo Runners takes place this tomorrow, 28 October in honor of Breast Cancer Month. Proceeds benefit the Breast Cancer Foundation of Egypt (BCFE). The 6 km run in SODIC West (Google Map) begins at 7:45am. Drive out yourself, or catch a ride with SODIC — the event’s Facebook page lists 6:30am pickups in Heliopolis, Lebanon Square and Nasr City. Stick around for post-run refreshments and a live music performance. Last year’s event was a blast, and you’ll do good in the process — trust us, it’s worth getting out of bed. Can’t make it but want to make a donation? The Facebook page lists BCFE accounts at CIB and other banks near you.

It’s MacBook Pro day. If we owned a black turtleneck, we’d wear it this morning. You can catch the unveiling tonight at 10am PDT (7pm CLT), with the livestream here.

Is it going to rain? We really have no clue. A couple of hours before dispatch time, and Google is showing sunny skies today and all weekend in Cairo. AccuWeather is showing a 50% chance of rain with thunder and lightning from noon until mid-afternoon. And the National Weather Service has forecast rain and warm temps in the capital city today and tomorrow. All we know is that with the breeze and cooler temps yesterday — and with the simple fact that we’re writing a weather advisory this morning — is that it is finally that three-week period in Cairo known as “fall.”

** A BRIEF PROGRAMMING NOTE: There will be no Weekend Edition tomorrow — we’ll be back on Sunday morning at the usual time. The Weekend Edition will return next Friday (a week from tomorrow) at about 10:30am.

** Oh, and sometimes we’re idiots. As just now, when one of realized none of us had arranged the draw for the winners of the Enterprise mugs. We’ll have names on Sunday, we promise.

A Contrarian View

CBE Corridor Rate hikes make a bad situation worse

Our mini-rant of yesterday on the futility of interest rate hikes set off a conversation with one of our favourite readers. The reader, a finance-industry insider well-known to many Enterprise subscribers, thinks we didn’t take our point all the way home.

** Do you have a point of view you would like to share — bylined or (if we’re convinced you’re not being malicious) on a no-name basis? Drop us an email: patrick@enterprise.press.

CBE Corridor Rate hikes make a bad situation worse

There’s a big difference between “corridor rate” and the general term “interest rates”.

The corridor rate is the rate that banks use as a reference for pricing all private-sector lending and, by extension (though not automatically), what they bid on treasury bills and bonds. Just saying “interest rates” refers to every type of rate. But which ones are more relevant to the case at hand?

Let’s look at the objective: Clearly, the issue is to defend the EGP at a time when there’s pressure to devalue. The logic is this: Raise rates people get on EGP assets and they will be less inclined to hold USD at zero interest. But which ‘people’?

The Central Bank of Egypt has raised the reference corridor rate (and the discount rate) by 300 bps in the past 10 months. In the same period, treasury bill rates rose about 4%. The average rates banks offer depositors across the sector barely rose — in some cases 1% or 2% for short-term deposits; longer term CDs haven’t moved much.

Who finds the EGP more attractive in this scenario? No one. If you don’t transmit (or limit) interest rate increases to the retail base (around 65% of private money in the banking system), then you’re only targeting treasury bill investors (mostly banks), hoping that foreign money goes there. Investors in short-term hot money to support the EGP? They still didn’t come. On the other hand, the government and the entire private sector are suffering from an aggressive rise in borrowing costs.

Or are we trying to stifle the economy to somehow force a reduced demand for USD? I hope not.

Any further increase in the corridor rate by the CBE (and any resulting increase in t-bill rates) will only do harm. The notion that you have to raise rates to fight inflation misses the point: Not all inflation is created equal. Inflation due to devaluation, and a resulting growth in money supply, has a ‘reset’ effect. That’s not the same as an overheating economy, which can cause rolling inflation. Should a devaluation see the EGP fall to a rate at which it can settle, there’s no further inflation from that cause. If, on the other hand, a devaluation is less than satisfactory to the market, and we try to increase rates to help make it satisfactory, we will end up worse off.

The best way forward after a devaluation is to (a) make the investment environment more attractive, which is helped by lowering borrowing costs and (b) making savings in EGP attractive by passing enough of the previous rate increases to the depositors.

Who might not like this? Banks, who have been the happy beneficiaries of large increase in margin between the cost of deposits and their return on government lending. But the good news is, banks were doing fine when their margin was thinner. Lending to the corporate and investment sector would increase, and so would the return on savings. In parallel, the government could slash 10s of bns off the budget deficit.

Part of the CBE’s role is to supervise and ensure a healthy banking system. It’s in good shape. The economy is not.

Speed Round

Edita has its sugar back. High-profile snack-foods maker Edita disclosed yesterday that the Prosecutor General’s Office had ordered released some 2k tons of sugar ordered seized on Saturday by a government inspection committee. Operations were set to resume at its Beni Suef candy factory “within hours,” Reuters reported. Hani Berzi spoke for most all of us when he noted that, “We are grateful for the personal attention paid to our issue by a number of senior government officials, who clearly understand the definition of private property and of a free market economy.”

The government’s inability to nip the sugar shortage in the bud and concern about 11 November protests prompted the seizure, said Alaa El Bahay, Chairman and CEO of Mass Food and a board member at the Food Export Council. Meanwhile, the Egyptian Businessmen’s Association joined the Federation of Egyptian Industries and the Chambers of Commerce in denouncing raids on factories to seize sugar, calling the move “unstudied” and saying, Al Borsa reported.

While we have (so far) seen no sign that the 11 November protests are anything more than the bogeyman of the night-time talk show hosts, the government has been using the multi-party youth conference in Sharm El Sheikh as a platform to reassure the public that it will reassure lower income earners and the poor from inflation. The protests are the backdrop to much of the coverage of the issue in the domestic press. President Abdel Fattah El Sisi announced on Tuesday that the government will sell at half-price some 8 mn food packages containing sugar, rice, tea, lard and tomato sauce, AMAY reports. Electricity Minister Mohamed Shaker promised to maintain electricity subsidies for lower-tier consumers, Al Shorouk added. Supply Minister Mohamed Ali El Sheikh, who did not attend the gathering, also promised to maintain subsidies under the smart card and bread point systems, the newspaper reports. Finance Minister Amr El Garhy chimed in by saying that the government is moving away from relying on grants and loans from abroad and instead is focusing on potential growth opportunities and funding in Egypt.

In other commodity-related news, state wheat buyer GASC made its largest wheat buy in two years. The world’s largest wheat buyer stocked up on 420k tons of Russian and Romanian, Bloomberg reported. “We think Egypt is playing catch up after cancelling / passing on multiple cargoes in September and late August,” Terry Reilly at Chicago broker Futures International told Agrimoney.com. Playing catch-up after the ergot flap may be part of it, but we think it has at least as much to do with the state padding its larder ahead of devaluation: Prime Minister Sherif Ismail announced last week that the central bank has allocated USD 1.8 bn for the buildup up of a six-month reserve of strategic supplies.

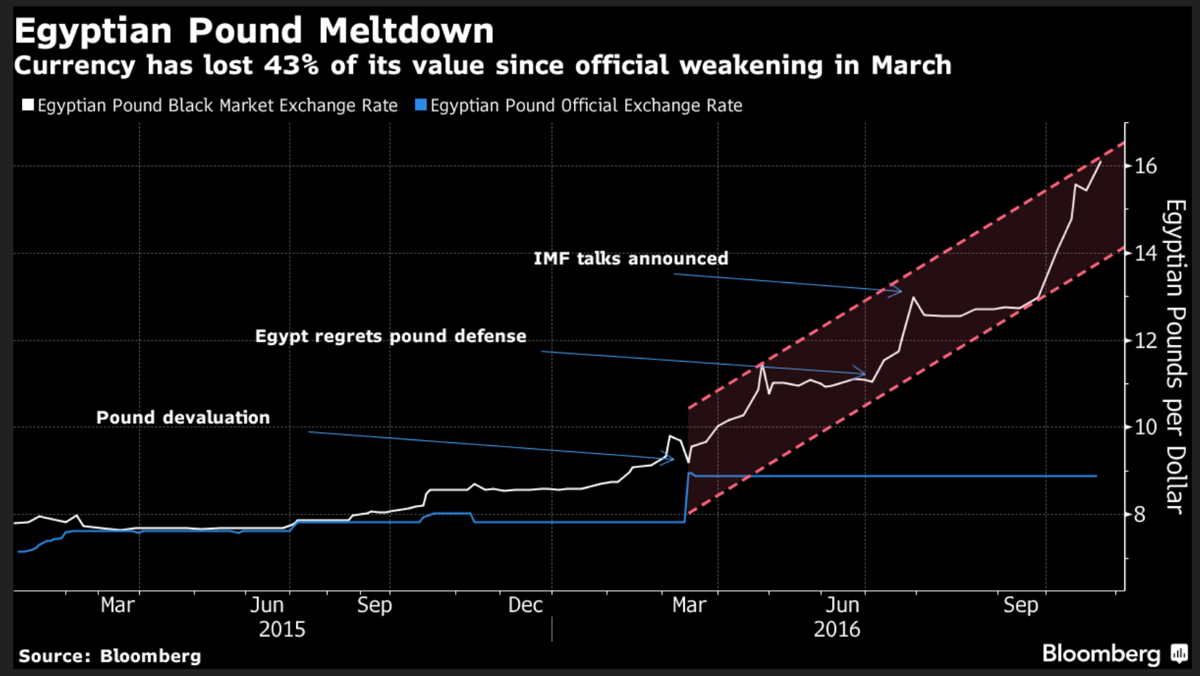

The wheat buy comes as the EGP hit what Bloomberg’s Ahmed Namatalla reports is another record low yesterday at 16.11 to the greenback (chart below). The EGP has shed 19% of its value against the USD on the parallel market in the past month and has “lost 43% of its value since the official weakening in March,” Namatalla notes. Al Borsa put the rate at EGP 16.40, while Al Mal put it at 16.35. The parallel market stood at EGP 16.20 to the greenback on Tuesday.

Speaking at the youth conference in Sharm, President Abdel Fattah El Sisi held the media partially responsible for the increased speculation in the parallel market. The EGP’s downward spiral began with the news, said the President, who was commenting on what he believes is the media’s propensity for exaggeration, AMAY reports.

Where do we go from here? EGP at 11.75, devaluation by mid-November and a 200 bps rate hike -Pharos. Radwa El-Swaify, head of research at Pharos Holding, thinks mid-November would be a “perfect time” for devaluation, noting that the central bank has gone beyond the originally implied timeline of mid-October. That, she tells Bloomberg’s Yousef Gamal El-Din (watch, run time: 4:22), has driven the parallel market rate north of EGP 16 to the greenback. “There’s no more room for delays,” El-Swaify says, explaining a mid-November devaluation would be “right before the [Central Bank of Egypt’s Monetary Policy Committee] meets on 17 November, when they should go for a rate hike of around 200 bps. It’s also before a planned IMF executive board meeting to discuss the package for Egypt.” Gamal El-Din noted that 12 month non-deliverable forwards on the EGP are at 13.76, prompting El-Swaify to suggest, “we’re looking at somewhere around 12. That’s where the three-month NDF is now.”

Finally, inflation is the subject of veteran financial writer Patrick Werr’s weekly column on the Egyptian economy for The National. Werr asks whether “the government [will] be able to keep money supply under control once an IMF deal is signed. The problem is the huge deficit, which has forced it to borrow directly from the central bank, or, in other words, essentially to print money.” The M2 money supply is up 18% in 8M2016, he notes, suggesting the Ismail government should “be able to use some of the bns it will receive under the IMF deal to plug the deficit without resorting to money creation” and, in turn, fueling inflation.

Eastern Tobacco raises specter of production shutdown, then backtracks: Eastern Tobacco Company reported a drop in days of production inputs on hand and raised the possibility of idling its factory lines if the FX situation continues, the company said in bullet points to explain its 2015-2016 results in regulatory filing with the Egyptian exchange (page 4, Arabic, pdf). The document notes that inventory of “primary manufacturing inputs that do not have a local alternative decreased to less than 6 months, which means that in the event that this situation continues for an extended period, the company will consider stopping producing and stop selling an important commodity to the consumer,” the company said. Eastern has said it is owed USD 32 mn by Philip Morris for July, August and September, as the company stopped accepting EGP for cigarettes it produced for the global brand. Al Masry Al Youm and Reuters picked up the report.

Company chairman Mohamed Osman later told Al Masry Al Youm the company hasn’t stopped manufacturing, adding that it has no issue with the availability of USD. What’s more, it has 12 months of tobacco on hand. He said the report included observations from the Central Auditing Organisation and that the company replied about them in the same report. There were indeed comments from the organization under “Auditor’s observations,” but that was on page 65 of the report.

“Today, Cairo is the fastest-growing city [for Uber] in Europe, Middle East and Africa … We’ve seen an uptick starting in 2016, which is the year it started booming,” Uber Egypt General Manager Anthony Khoury told Reuters. Uber are investing USD 50 mn into Egypt over the coming two years, as the centrepiece for its Middle East growth strategy that will see it invest USD 250 mn into the region over five years, he said. “The sharing economy in general is a completely new type of economy, so it’s usually a bit tricky at the beginning," he said. "But Egypt was very quick to see the benefits, create a cross-ministerial committee and start really trying to regulate the operation.” Uber are building a support center in Cairo that will serve the Middle East and parts of Africa, with its current staff of around 175 expected to reach 1,000 by the end of 2017.

Independent E&P outfit Apex International Energy has opened offices in Cairo and Houston, Texas, the company said in a statement (pdf), and is now on the hunt for assets. Backed by global private equity outfit Warburg Pincus, Apex “plans to build an exploration and production business of scale through asset acquisitions and capital investment.” Roger Plank, Apex’s founder and chief executive, notes that “With significant funding in place and the launch of our two offices … we have made Egypt our top priority place to invest and are actively involved in the current concession bidding round and evaluating a number of interesting acquisition opportunities.” Chief operating officer Tom Maher added that Apex is “present on the ground with local and growing teams in Cairo and Houston, two of the most important cities in the global oil and gas industry. We are currently working closely with government and local third parties in Egypt as we take an active role in developing our business.” Warburg Pincus has more than USD 40 bn in private equity AUM and a portfolio of over 120 companies.

Real estate developer Misr Italia and a cement company listed on the Egyptian Exchange before year-end, with listing procedures are underway, EGX president Mohamed Omran told Reuters in a piece picked up by Al Borsa. The EGX is seeking a link with the Bahrain Bourse in 1H17 which would allow Egyptian investors to trade there through brokers and vice versa; an EGX delegation visited Bahrain recently. (We have zero inside information, but would caution that while Misr Italia may obtain approval to list, that’s very different from it pulling off an IPO in the current climate. We remain pretty bearish on the outlook for IPOs in the next few months — we need to pull off devaluation a convincing devaluation and show a few months of stability before any offering that comes to the market would look (a) appealingly priced and (b) sufficiently de-risked from the FX side of the equation.)

PHD’s Abdel Rahman looks to mega deal, sees real estate prices will start to plateau. "There is still room for prices to go a bit higher but at a certain point it will plateau … Instead of seeing 30 percent year over year, you may start seeing 20 percent," co-CEO Tarek Abdel Rahman told Reuters as part of the newswire’s Middle East Investment Summit. The company also expects to sign by year’s end an agreement on what it thinks would be the country’s second-largest real estate project. Reuters reports “the site covers 25 million square meters — equivalent in size to about a third of Dubai — and will include residential and commercial facilities.

Al Futtaim Automotive has ordered the recall of six Honda models to inspect and replace airbags as part of a wider recall ordered by the Japanese automaker, Al Mal reported. The models in question are the Accord models 2004-2009, City models 2008-2013, Civic models 2002-2010, CR-V models 2002-2009, Jazz models 2002-2005, and the Stream 2002 model. The company is replacing all airbags on all models at no cost to car owners.

Is the pay-in-advance offer for global shippers a bid to stock-in USD, or a pre-emptive strike against the Panama Canal? As we’ve noted several times in recent weeks, the Suez Canal Authority is offering major global carriers 3% discounts on transit fees in return for a 3-5 year pre-payment of fees. Local analysts (ourselves included) have largely positioned this in the context of the nation’s FX woes — building the CBE’s war chest today with tomorrow’s revenues. The WSJ suggests it could just as easily be the SCA looking to lock-in market share amid rising competition from the Panama Canal during the current market downturn. Egypt is also benefitting from the resurgence of US oil and gas producers, SCA chief Mohab Mamish notes: “The Suez is counting heavily on increased petroleum-product cargoes such as liquefied natural gas and ethanol from the U.S. to Asia in coming years, as US energy exporters are tapping new markets in Asia. ‘The exports by US refiners to Asia, and especially countries like India, will boost our revenue significantly,’ Mr. Mamish said.” See stories in the Journal here and here.

Heineken CEO re-ups for another four-year term: Elsewhere in the Journal, weaker sales in Egypt, Russia and the Democratic Republic of Congo are behind declining volumes for Heineken in the third quarter, the paper notes in a piece on the brewer’s decision to stick with its “seasoned” CEO: “Heineken said Wednesday it would seek a rare fourth, four-year term for Chief Executive Jean-François van Boxmeer, who has led Heineken since 2005.” The catalyst: The growing turf battle with Anheuser-Busch InBev.

Six renewable energy firms signed power purchase agreements under phase one of the feed-in tariff program for renewable energy by yesterday’s deadline. Nine others withdrew from the program, but could still participate in phase two. Companies have until today to announce they have reached financial close on their projects; any company not doing so can carry forward to phase two, which has different terms. Energy producers signing yesterday included: Scatec Solar, Infinity Solar, Elf Energy, ARC Renewable Energy, Austrian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA), and Nubian for Renewable Energy, Al Borsa reported, adding that Scatec, Infinity, Nubian and ARC are the most likely to complete financial close by today. Companies withdrawing from phase one (most of this has previously been reported):Italy’s Enel Green Power, France’s Neon, KSA’s Abdel Latif Jameel Energy, Egypt’s Cairo Solar, Spain’s Dhamma Energy, Conrad-Canadian Solar, Innovation Unlimited Egypt, the UAE’s Adenium Energy Capital and OTMT. Eighty companies and consortia who are qualified for FiT will continue into the second phase, including Elsewedy Electric, Orascom Construction, Philadelphia Energy, ACWA Power, Al-Tawakol for Electrical Industries and Lekela Power, Al Borsa reported.

Picking up where we left off yesterday, the Electricity Ministry is studying proposals from six companies to build a 6,000 MW clean coal power plant with an investment value of USD 10 bn, Al Borsa reports. All the projects are set to be executed under the EPC+Finance system. The Electricity Ministry is aiming to generate 7,000 MW from clean coal power plants by 2023. The full breakdown of competing companies and consortia:

- Shanghai Electric: Proposed building a 4,640 MW plant in Hamrawein at USD 7

- Dongfang Electric: Proposed 6,000 MW plant in Hamrawein, investment value not revealed

- Harbin-General Electric: Proposed 6,510 MW plant at USD 8 bn.

- ElSewedy-Marubeni: Signed an MoU to build 4,000 MW power plant in West Marsa Matrouh.

- Mitsubishi-Hitachi: Proposed 4,000 MW plant in Marsa Matrouh.

- Sumitomo: Proposed 2,000 MW power plant in Marsa Matrouh.

Saudi Arabia’s aviation authorities have finally approved flight schedules for private Egyptian airlines running routes to Saudi Arabia for the winter season, said the head of the Civil Aviation Authority Hany El Adawy, according to Al Mal. The move follows delays in the approval which many in the media have speculated was due to the reported rift in relations between Egypt and Saudi Arabia. In other Saudi news, the power grid link with Saudi Arabia will be operational in 2019, said Deputy Electricity Minister Osama Esran at the China-Arab States Cooperation Forum, Al Shorouk reports. Last week, a Saudi delegation visited Egypt to jointly reviewing bids on installing transformers for the Saudi-Egypt power grid link. Bidders include Siemens, ABB Group, and Alstom.

On Deadline

Al Ahram columnist Farouk Goweda asks how the government has not been able to clear the Black Cloud over Cairo for 20 years. The phenomenon resulting from burning rice straw after the rice harvest each autumn has been estimated by environmentalists to cause 42% of the city’s pollution. The cost of treating people’s illnesses resulting from the noxious smog are surely higher than an effective waste management system, he says.

Worth Watching

Somebody beats us to the punch: We had previously thought up a plan to use our recording studio as a panic room in times of stress, but a bookstore named “The World’s Door” did just that, according to Reuters. A dark, soundproof room, complete with a drum kit, where each visitor gets ten minutes, free of charge, to “scream at the top of their lungs in an effort to relieve their frustrations and escape from the stresses of daily life.” Sold. (Watch, run time: 0:44)

Diplomacy + Foreign Trade

A delegation of top executives from 15 Slovenian companies is visiting Egypt in early December, Trade and Industry Minister Tarek Kabil told Al Mal. The ministry is expecting to sign MoUs to expand investment and bolster cooperation on consumer protection, he added. Delegates will include agriculture and electricity companies. Kabil called for setting up a Slovenian-Egyptian Business Council.

Energy

EGPC signs partnership agreement with Kuwait Energy over Siba Field in Iraq

EGPC signed a partnership agreement with Kuwait Energy over the development of the Siba natural gas field in Iraq, which would see the EGPC receive 20% of the field, according to Reuters which cites a statement by Kuwait Energy. Al Mal puts the EGPC’s partnership stake at 15% of the 555 bcf reserves and 37 mn bbl of condensates. Petrojet is the primary contractor for the project, and has estimated operations of around USD 200 mn. The project is the second partnership between EGPC and Kuwait Energy outside Egypt.

Infinity Solar presents bid to build 50 MW solar power station in Fayoum under FiT phase 2

Infinity Solar have presented a proposal to the NREA to build a 50 MW solar power plant in Fayoum under phase two of the Feed-in Tariff Project, Al Mal reported. The project has an estimated investment cost of USD 100 mn, sources the Electricity Ministry said. Infinity Solar already signed the power purchasing agreement for FiT phase one and is building a separate 50 MW solar power plant in Benban. The Electricity Ministry has so far received notification from 15 companies to participate in FiT phase two, the source added.

Basic Materials + Commodities

Egypt is 100% self-sufficient from table eggs, 90% livestock, 80% dairy

The government continues to beat the drum of self-sufficiency heading into devaluation, with the Agriculture Minister announcing (rather out of the blue) that Egypt is 90% self-sufficient when it comes to livestock and poultry, 80% in dairy products — and 100% when it comes to table eggs. With 8 bn eggs a year produced in Egypt, we can start exporting, the ministry suggested. Al Shorouk has more. As if we needed another reminder that there is enough eggs in the country.

Manufacturing

SE Wirings inaugurates EGP 300 mn factory expansion

SE Wiring Egypt inaugurated an EGP 300 mn expansion of its car wiring harnesses factory in Port Said, Al Mal reported. The expansions included two new production lines, one specifically for Honda vehicles, said head of free zones at GAFI Hossam Haddad. The company is planning to open a second factory in the Tenth of Ramadan industrial city, he added.

Iraq, Jordan, and Lebanon delaying import approvals for new Egyptian food companies

Iraq, Jordan, and Lebanon have been delaying import approvals for new Egyptian food companies to export dairy products to said markets, Food Export Council Chairman Hani Berzi tells Al Mal. This comes despite these companies having reportedly fulfilled necessary requirements and met standards. He urged Egyptian authorities to press these countries to approving the exports.

Health + Education

DBK Pharma invests EGP 200 mn into veterinary vaccines

DBK Pharma is investing EGP 200 mn to establish a veterinary vaccine production line at its factory in Obour, company sources told Al Mal. DBK will finance the production line through export revenues, the source added. Egypt imports 80% of its veterinary vaccines, but the project aims to provide 40% of the demand, the source said. The company is presenting a fair-value report to the EFSA by the end of the week, and will decide on what percentage to IPO at its next board meeting.

Pharmacists Syndicate to press legal charges against 40 pharma companies

The Pharmacists Syndicate is filing a lawsuit against 40 manufacturers for not complying with directive 499, which aims to increase the profit margins for pharmacies by having manufacturers and distributors provide them discounts and commissions, Al Borsa reports. The always-litigious syndicate is also planning on bringing a case against the Health Minister for failing to enforce the directive, especially since the ministry agreed to raise prices of meds sold for under EGP 30 by 20% back in May, said member Mohamed El Rifay. The syndicate has also voted to suspend its planned boycott of pharma companies which have not complied with the decision until the syndicate’s general assembly, he added.

Tourism

TUI Belgium resumes flights to Sharm El Sheikh on Sunday

Travel company TUI Belgium are resuming direct flights to Sharm El Sheikh on Sunday after a year-long hiatus, the Tourism Ministry told Al Mal. TUI will send two weekly flights from Brussels to Sharm El Sheikh during the winter season, the ministry added.

Tourism Ministry reduces incentives on charter flights

The Tourism Ministry has reduced the incentives offered to charter airlines to USD 2,000 per flight from a previous USD 3,000, according to Al Borsa. The ministry has also raised the minimum capacity a carrier had to reach before qualifying for the subsidy: 80% of seats must be filled for flights to Sharm El Sheikh and Hurghada airports, up from 70%. The Ministry, however, reduced the requirement to 50% for flights to Al Alamein, Marsa Matrouh, Luxor and Aswan.

Telecoms + ICT

Oppo still considering assembly plant in Egypt, established regional marketing center

Chinese smartphone manufacturer OPPO is “seriously considering” establishing a mobile phone assembly plant in Egypt for domestic consumption and export to the MENA region, Al Masry Al Youm reported. OPPO recently established its regional marketing center in Egypt to “better understand” the Egyptian, Moroccan, Algerian, Qatari, and Emirati markets

China’s Inspur in talks with CIT ministry to expand investments in region including Egypt

Chinese IT multinational Inspur wants to expand its investments in the region, have its Middle East headquarters location in Egypt, and build a new factory, top Inspur executives told Communications minister Yasser El-Qady in a meeting reported by Al Borsa. They also met with ITIDA (Information Technology Industry Development Agency) Asmaa Hosny, where they discussed establishing an electronics factory and a governmental data center in Borg El-Arab city.

Automotive + Transportation

EAMA and Trade Ministry discuss automotive directive executive regulations

The Egyptian Automobile Manufacturers Association (EAMA) and the head of the Industrial Development Authority held talks yesterday to discuss their proposals for the executive regulations of the automotive directive, Al Mal reports. The Trade and Industry Ministry is planning to form a committee to draft the regs and is meeting with industry to gauge their opinions. EAMA has raised some objections of the automotive directive which it hopes would be addressed in the regs, said Hassan Suleiman head of EAMA. these include clarifying whether imported parts that contain some local components will be classified as a locally sourced goods. The law plans to raise the portion of locally sourced components in car manufacturing to 60% from 45%. Export incentive structures must also be clarified, an unnamed member of EAMA tells the newspaper. The Trade and Industry Ministry was supposed to have begun drafting the regulations back in September, according to statements by minister Tarek Kabil.

CKYHE shipping alliance returns to East Port Said in March after two year hiatus

The CYKHE shipping alliance is returning its base of operations to East Port Said in March, sources told Al Mal. Long waiting times at the port forced the alliance to reroute operations to Greece in 2015, which in turn dropped the Suez Canal Container Terminal to 1.8 mn containers from 3.4 mn in 2014. The alliance consists of Cosco Container Lines, "K" Line, Yang Ming Line, Hanjin Shipping, and Evergreen Line.

Bidding on ITS for new Regional Ring Road to open soon

The General Authority for Roads, Bridges and Land Transport will launch a global tender for “intelligent transportation systems” (ITS) on the new Regional Ring Road that “extends from Belbees City to Eastern Cairo city to El Sadat city in the western fringe of the Nile Delta” and on Shobra-Banha road, Authority chairman Adel Tork said, Al Borsa reported. The bidding terms are ready. Here is a 2010 report (pdf) on ITS from India’s Centre of Excellence in Urban Transport if, you know, you’re interested.

Other Business News of Note

Badr City investors complain of brownouts

Investors and businessmen in Badr City have complained that they are facing brownouts that have damaged machinery and hindered production, Badr City’s Investors Association Chairman Bahaa El Adly said, according to Al Mal.

Tahya Misr fund has collected EGP 7.5 bn

The Tahya Misr fund has collected EGP 7.5 bn of the president’s targeted EGP 100 bn, the fund’s executive manager, Mohamed Ashmawy said in an interview on Al Hayat (runtime: 0:44).

Legislation + Policy

House committee wants to tax SMEs 10%

The House’s Planning and Budget Committee is inclined to lower the tax on SMEs to 10% down from 22.5%, undersecretary Yasser Omar said, Al Borsa reported. Omar expects the Cabinet to refer the law to the House before year-end. Committee member Talaat Khalil called for lowering interest rates for SME loans, too. (Don’t get your hopes up, entrepreneurs. Our take: They’re probably going to define an “SME” as anything that makes less than EGP 500k a year.)

Egypt Politics + Economics

Gov’t exploring options to collect EGP 70 bn in back taxes

The Finance Ministry is exploring the most appropriate method to collect EGP 70 bn in back taxes owed by government bodies and the private sector, Al Shorouk reports. The ministry is mulling over options which include adopting incentives to encourage payment, getting into settlement proceedings presumably under the Tax Disputes Settlement Act, or wiping the slate clean for those incapable of paying the taxes, said Deputy Finance Minister Amr El Monayer. EGP 14 bn in back taxes are owed by the private sector and individuals, while EGP 25-30 bn in taxes are owed by people and companies which have gone bankrupt or died. State-owned companies and other bodies owe around EGP 30 bn, said El Monayer.

Ismail cabinet expected to postpone first quarterly report on progress of its agenda to the House

The Ismail cabinet is expected to postpone presenting its quarterly report on the status of the government plan to the House of Representatives until it signs for and receives the first payment of the USD 12 bn IMF facility, devalues the EGP, and the partial rationalization of subsidies, cabinet sources tell Al Shorouk. The Ismail cabinet had promised to present to the House quarterly updates on the progress of the reform agenda back when it first presented it in March (check out our spotlight on the program for a refresher). The cabinet had formed a committee made up of representatives from the ministries to compile the report.

Court of Cassation upholds Mohamed Badei’s life sentence

Egypt’s Court of Cassation upheld yesterday the life sentence imposed on former Muslim Brotherhood supreme guide Mohammed Badie in 2013 for inciting deadly violence, Ahram Online reports. The life sentences on 36 other defendants for similar charges was also upheld. This would be the first final ruling against Badei in a series of retrials for various criminal cases. Earlier this week, the court confirmed a 20-year sentence against former president Mohamed Morsi.

On Your Way Out

The Tourism Ministry released its newest advertisement (runtime: 1:24) for the “This is Egypt” campaign, with far more impressive cinematography than last year’s.

The markets yesterday

USD CBE auction (Tuesday, 25 Oct): 8.78 (unchanged since 16 March 2016)

USD parallel market (Wednesday, 26 Oct): 16.40 (from 16.10 on Tuesday morning, 24 Oct, Al Borsa)

EGX30 (Wednesday): 8,257.21 (-0.05%)

Turnover: EGP 476.05 mn (29% above the 90-day average)

EGX 30 year-to-date: +17.85%

Foreigners: Net short | EGP -43.7 mn

Regional: Net short | EGP -16.9 mn

Domestic: Net long | EGP +60.6 mn

Retail: 55.7% of total trades | 55.8% of buyers | 55.6% of sellers

Institutions: 44.3% of total trades | 44.2% of buyers | 44.4% of sellers

Foreign: 15.6% of total | 11.7% of buyers | 19.5% of sellers

Regional: 13.1% of total | 11.6% of buyers | 14.6% of sellers

Domestic: 71.3% of total | 76.7% of buyers | 65.9% of sellers

***

PHAROS VIEW

Devaluation in the Driver’s Seat

Stocks that have risen YTD are mostly devaluation beneficiaries, whose sources of FX outweigh their FX costs; or whose revenues and costs are FX based, due to foreign operations / export orientation / import parity pricing. Failure to determine the point of stability for the exchange rate will create support for share price performance of that group. Pharos believes that with the market now losing steam, investors should seize rebounds to partially offload their positions, outlining six factors that Pharos Head of Research Radwa Swaify believes will cap market performance beyond the upper boundary of the 7,900 to 8,500 range. The note also outlines “Names we continue to like despite the rally and names that have not rallied, but which we want to flag” — as well as the “laggards” of 2016 who look set to become next year’s stars. Tap or click here to read the full note.

***

WTI: USD 49.19 (+0.02%)

Brent: USD 50.01 (+0.06%)

Natural Gas (Nymex, futures prices) USD 2.74 MMBtu, (+0.37%, November 2016 contract)

Gold: USD 1,267.00 / troy ounce (+0.03%)<br

TASI: 5,885.0 (0.0%) (YTD: -14.9%)

ADX: 4,265.8 (0.0%) (YTD: -1.0%)

DFM: 3,304.2 (-1.0%) (YTD: +4.9%)

KSE Weighted Index: 359.4 (+1.2%) (YTD: -5.8%)

QE: 10,362.7 (-0.4%) (YTD: -0.6%)

MSM: 5,513.7 (-0.2%) (YTD: +2.0%)

BB: 1,144.9 (+0.1%) (YTD: -5.8%)

Calendar

24-27 October (Monday-Thursday): European Bank for Reconstruction and Development is in Cairo to discuss opportunities to “intensify its activities” in Egypt.

24-29 October (Monday-Saturday): The 2016 Dubai Design Week Iconic City exhibition Cairo NOW City Incomplete, Dubai Design District (d3), Dubai

26-27 October (Wednesday-Thursday): The Marketing Kingdom Cairo 2 event, Cairo.

31 October (Monday): Deadline for Telecom Egypt to reach an agreement with MNOs over using their 2G and 3G network infrastructure

November (TBD): Delegation of German companies in the renewable energy sector due to visit to discuss investment opportunities.

2-6 November (Wednesday-Sunday): Petroleum Housing Conference, Petrosport Club, New Cairo, Cairo

3 November (Thursday): The Emirates NBD PMI for Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the UAE compiled by Markit comes out here.

14-16 November (Monday-Wednesday): Bank of America Merrill Lynch MENA 2016 Conference, The Ritz Carlton, Dubai International Financial Centre, Dubai.

17 November (Thursday): Central Bank of Egypt’s Monetary Policy Committee meets to review rates.

25-26 November (Friday-Saturday): 27th Energy Charter Conference, Tokyo, Japan.

27 November (Sunday): 2016 Cairo ICT, Cairo International Convention Centre.

29-30 November (Tuesday-Wednesday): Citi’s Global Consumer Conference, London, UK.

04-06 December (Sunday-Tuesday): Solar-Tec exhibition, Cairo International Convention Centre.

04-06 December (Sunday-Tuesday): Electricx exhibition, Cairo International Convention Centre.

07-08 December: Citi’s 2016 Global Healthcare Conference, London, UK.

10-13 December (Saturday-Tuesday): Projex Africa and MS Marmomacc + Samoter Africa, Cairo International Convention Centre.

11 December (Sunday): Prophet Muhammad’s Birthday (national holiday; date to be confirmed).

11-13 December (Sunday-Tuesday): The Middle East Fire, Security & Safety Exhibition and Conference (MEFSEC), Cairo International Convention Centre, Cairo.

13 December (Tuesday): Amwal Al Ghad’s top 50 most influential women in Egypt women forum, Four Seasons Nile Plaza Hotel, Cairo.

29 December (Thursday): Central Bank of Egypt’s Monetary Policy Committee meets to review rates.

14-16 February 2017 (Tuesday-Thursday): Egyptian Petroleum Show, Cairo International Convention and Exhibition Centre.

Enterprise is a daily publication of Enterprise Ventures LLC, an Egyptian limited liability company (commercial register 83594), and a subsidiary of Inktank Communications. Summaries are intended for guidance only and are provided on an as-is basis; kindly refer to the source article in its original language prior to undertaking any action. Neither Enterprise Ventures nor its staff assume any responsibility or liability for the accuracy of the information contained in this publication, whether in the form of summaries or analysis. © 2022 Enterprise Ventures LLC.

Enterprise is available without charge thanks to the generous support of HSBC Egypt (tax ID: 204-901-715), the leading corporate and retail lender in Egypt; EFG Hermes (tax ID: 200-178-385), the leading financial services corporation in frontier emerging markets; SODIC (tax ID: 212-168-002), a leading Egyptian real estate developer; SomaBay (tax ID: 204-903-300), our Red Sea holiday partner; Infinity (tax ID: 474-939-359), the ultimate way to power cities, industries, and homes directly from nature right here in Egypt; CIRA (tax ID: 200-069-608), the leading providers of K-12 and higher level education in Egypt; Orascom Construction (tax ID: 229-988-806), the leading construction and engineering company building infrastructure in Egypt and abroad; Moharram & Partners (tax ID: 616-112-459), the leading public policy and government affairs partner; Palm Hills Developments (tax ID: 432-737-014), a leading developer of commercial and residential properties; Mashreq (tax ID: 204-898-862), the MENA region’s leading homegrown personal and digital bank; Industrial Development Group (IDG) (tax ID:266-965-253), the leading builder of industrial parks in Egypt; Hassan Allam Properties (tax ID: 553-096-567), one of Egypt’s most prominent and leading builders; and Saleh, Barsoum & Abdel Aziz (tax ID: 220-002-827), the leading audit, tax and accounting firm in Egypt.